Written by Peter Harding and Tinsa Harding.

Illustrations by Genevieve Shapiro

“He who is outside the door has already a good part of the journey behind him.”

~ Dutch Proverb

Introduction

Some readers may remember Pete Harding from my inaugural Unbreaking News post in late July describing his exploits in Bolivia. I return to Pete for the holiday season, this time in his own words. Pete wrote this motorcycle diary/memoir several years back, and was on the verge of getting it published in a prestigious motorcycle magazine based in the UK. But the editor balked at the last minute, requesting photographic proof of the story’s veracity before agreeing to publish. Alas, photos were one thing Pete didn’t have. He searched through boxes and sifted through files and folders but came up empty. Instead of calling it quits, Pete turned this problem into an opportunity. He reached out to our friend and former colleague Genevieve Shapiro (we all worked together in Peru) to see if she might be willing to grace his story with a few delightfully distinctive drawings where the photos would have been. A brilliant artist with an original spirit and a quirky wit that come across clearly in her work, Genevieve agreed. I believe the results speak for themselves.

One final word. I’ve sometimes thought that the best preparation for the foreign service is not (necessarily) an advanced degree from a fancy university, but rather wide and varied human experience across the board. Whatever our technological advances in this era of algorithms and artificial intelligence, we still live in a world of people and places and concrete things—a real world, not a virtual one. Getting your hands dirty, working in unconventional circumstances with unconventional people, finding yourself in a place you never figured you’d be and doing your best to do the right thing, these and similarly uncharted experiences may be the most instructive and valuable of all. Pete has precisely this kind of experience in spades, which made him a superb dusty roads diplomat if not always the most enthusiastic memo-writing bureaucrat.

Now, over to Pete, Tinsa, and Genevieve.

*****

Shipwrecked at Home

My undergraduate studies had been interrupted in the early 1970s when I was drafted into the U.S. Army for two years, including a tour in Vietnam. But when I returned to school, at least I got funding from the G.I. bill. I also found a part-time job towing vehicles on campus, which didn’t win me many friends but did help defray some expenses. So I was able to graduate debt-free from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, in 1976 with a B.A. in Latin American History.

Like others before and after me, I discovered that a liberal arts degree in History and 50 cents was not immediately marketable. It would buy me a cup of coffee but not much else. So at age 26, I found myself broke and living back at my parents’ house in Wellesley Hills, wondering what was next. I bristled at them telling me what to do, including chores around the house. I wanted to be independent but lacked the income to live on my own.

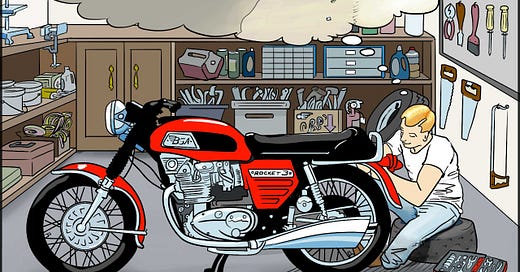

With the little money I did have and some borrowed from my younger brother Nick, who was working at a chemical factory at the time, I bought a disassembled 1969 three-cylinder 750cc BSA (Birmingham Small Arms) Rocket III motorcycle for $350. It was what people would call a real ‘basket case.’ The previous owner had blown up the engine and taken it completely apart, so the greasy parts were spread out pell-mell in baskets and cardboard boxes. But my experience as a motorcycle mechanic gave me the confidence to tackle this project.

After a month or so of assembling, repairing, and borrowing more money to buy spare parts, I managed to piece the bike back together. Finally, it was time to turn on the ignition and kick it over. To my delight, it started right up. There is no better feeling for a mechanic than the moment when a machine, long dormant and (as far as you know) maybe even dead, is brought back to life. The three-cylinder engine on this model of bike produced a gorgeous, full-throated sound that called to mind a low chorus of mountain lions and banshees.

The BSA Rocket III 750cc motorcycle first appeared in 1969 in a bright Ruby Red. An almost identical model, painted in a shade of aquamarine, was marketed under the Triumph brand called “Trident.” The bikes were England’s last stand against the onslaught of high-tech two-wheeled machines from Japan. Both the Trident and Rocket III sported dual exhausts with three distinctive pipes at the ends, dubbed “Flash Gordon” mufflers for obvious reasons. In my view, the 1969 BSA Rocket III was as classic a British-American beauty as Elizabeth Taylor.

Was it fate? At the very moment that the bike kicked back to life, my mother called me to say that a friend of mine named Pat Morley was on the phone from Leominster, MA.

I remember Pat telling me, “Boy am I tired of New England. The weather sucks, and there are no good jobs. I’m sick and tired of this place. I want to go to California, where the weather is nice, the girls are pretty, and the job prospects are better.” He then added, seemingly out of the blue, “Do you know anybody selling a good motorcycle capable of crossing the country?”

I said, “Let me check around, and I’ll call you back.”

Pat had mentioned the mythical word “California,” which brought back one of my earliest childhood memories. As a toddler, I would peer through the orange-gold handle of my toothbrush as though it were a telescope and say, from our home in Hartsdale, NY, “I see California!”

Sure, I had passed through Oakland Army Base and Travis Air Force Base to and from Vietnam, and I had made a cross-country trip by car with my friend Mark DeMaranville and spent a week or so in the Golden State some years before. But the word retained a special conjuring power in my imagination. Whether it was Jim Morrison’s “The West is the Best,” Frederick Jackson Turner’s “Manifest Destiny,” or the beach scene in Venice, who knows?

Coincidentally, around this same time I was offered a position at the prestigious Bank of Boston. Two neighbors, veterans of the Korean War who worked in senior positions at the bank, told my parents that a job there was mine if I wanted it.

My dad said, “Listen Pete, you only have a degree in History, and your GPA is not that great. In my experience, most good jobs are found through connections.”

So I got a haircut, put on my one and only suit, a tight-fitting light gray polyester beauty with wide lapels and bell bottom pants (as I recall), and showed up at the Bank of Boston Headquarters on Federal Street several days later. It was one of those tony downtown banks with thick-piled carpeting, dark wood paneling, and a solemn, hushed atmosphere.

In the office, my two neighbors said, “Pete, we’re good friends of your parents; your dad was in WWII, and you are a Vietnam veteran, so we’re going to give you a chance here. We’re going to offer you a good salary—you’re going to work half a day at the bank, and for the other half-day, we’re enrolling you in a Master’s level degree in International Finance, at our expense.”

When I came home, my parents said, “You should consider yourself lucky. Most of your friends would jump at this opportunity!”

But when I went back down to the basement garage, fired up the Red Rocket III, and listened to its beautiful sound, I suddenly saw myself, in my mind’s eye, thirty years from that moment, still living in Wellesley Hills, married, with 2.5 kids, driving one of those station wagons with faux wood on the side, and shuttling from the PTA meeting to the supermarket to the country club, and thought to myself, “No thanks.”

Instead, I picked up the phone and called my friend Pat Morley. “I know where there’s an excellent motorcycle, recently rebuilt, and at a very low price. I’ll sell it to you under one condition.”

Pat asked, “What’s that?”

“That I go with you.”

Pat wasted no time. He came over that very evening. I went upstairs to my room, grabbed a sleeping bag, some spare clothes, and a few other supplies, and strapped them onto the bike. When Pat showed up, it was raining outside and suddenly, unseasonably cold.

My parents asked, “What are you doing?”

“We’ve decided to go cross-country on this motorcycle—to California.”

My parents told me I was crazy, a fool. They pleaded for me not to go, listed a bunch of good reasons, but didn’t try to stop me outright. So we took off in the cold rain that very night. I drove and Pat sat on the back. After more than 300 miles and 7 hours on the road, we made it to Philadelphia.

Pat said, “I can’t take this anymore; I’m getting hypothermia.”

The next morning in downtown Philly I put him on a Greyhound bus heading west. We agreed to meet in San Francisco. Pat had already paid me cash for the bike.

*****

Alone On the Road

Now, I was on my own with the Red Rocket III.

On the way from Philly to Chicago, I thought I had discovered a clever trick that would help me over the long haul. By sneaking into the slipstream of the big semi-tractor trailer trucks on the freeway ahead of me, I noticed that if I came close enough to their large back bumper, the wind would die down and I would be pulled magically along in the air pocket. It was wonderful. But just on the outskirts of Chicago, the tread from one of the tires on the truck in front of me separated and flew off. The 50-pound piece of thick rubber tread, looking like a big black snake, flew right above my shoulder, barely missing me. At 70 miles per hour, it was a close call. I decided that my clever slipstream trick was too risky to continue.

Thanks to Pat I now had some pocket money. Still, I preferred to camp by the side of the road rather than pay for a motel. The Red Rocket III could climb up the steep footpath by the side of the road, and nose its way into the brush or woods no problem. There I would lay down my sleeping bag, where I remained practically invisible from the road.

*****

When I reached the border between Utah and Nevada at West Wendover on Route 80, I looked out over the desert and salt flats. I saw a bank of dark clouds on the horizon. But I told myself, “There’s no chance that it’s going to rain out here. I’m in the middle of the desert!” Boy, was I wrong.

Once in Nevada, a storm like the biblical end of the world erupted. Huge bolts of lightning flashed, thunder cracked and rolled, and thick sheets of water fell like a bucket being emptied. Before I knew it, the highway was six inches deep in water. There were practically no cars on the highway. I slowed down to a crawl.

The towns in Nevada are far apart. Passing through Battle Mountain, I was on my way to Winnemucca, some 50 miles away. But I just couldn’t make it any farther. It was about two in the morning, so I decided to pull into a 24-hour laundromat in town to dry off. I stripped off my sopping clothes—everything save a pair of bright orange plastic rain pants—and put them in the dryer. I had been so thoroughly soaked that my black leather jacket stained my torso a dark purple. Two elderly ladies happened into the empty laundromat just then, laundry baskets in hand. When they saw the big bike outside and the disheveled biker with bright orange rain pants and a chest dyed purple standing inside next to the dryers, they decided it would be better to do their laundry some other time. They turned around and walked out.

I later learned that the thunderstorm had caused a flash flood that washed out the Thompson River Canyon, erasing camping trailers from the landscape and killing 143 people, five of whom were never found.

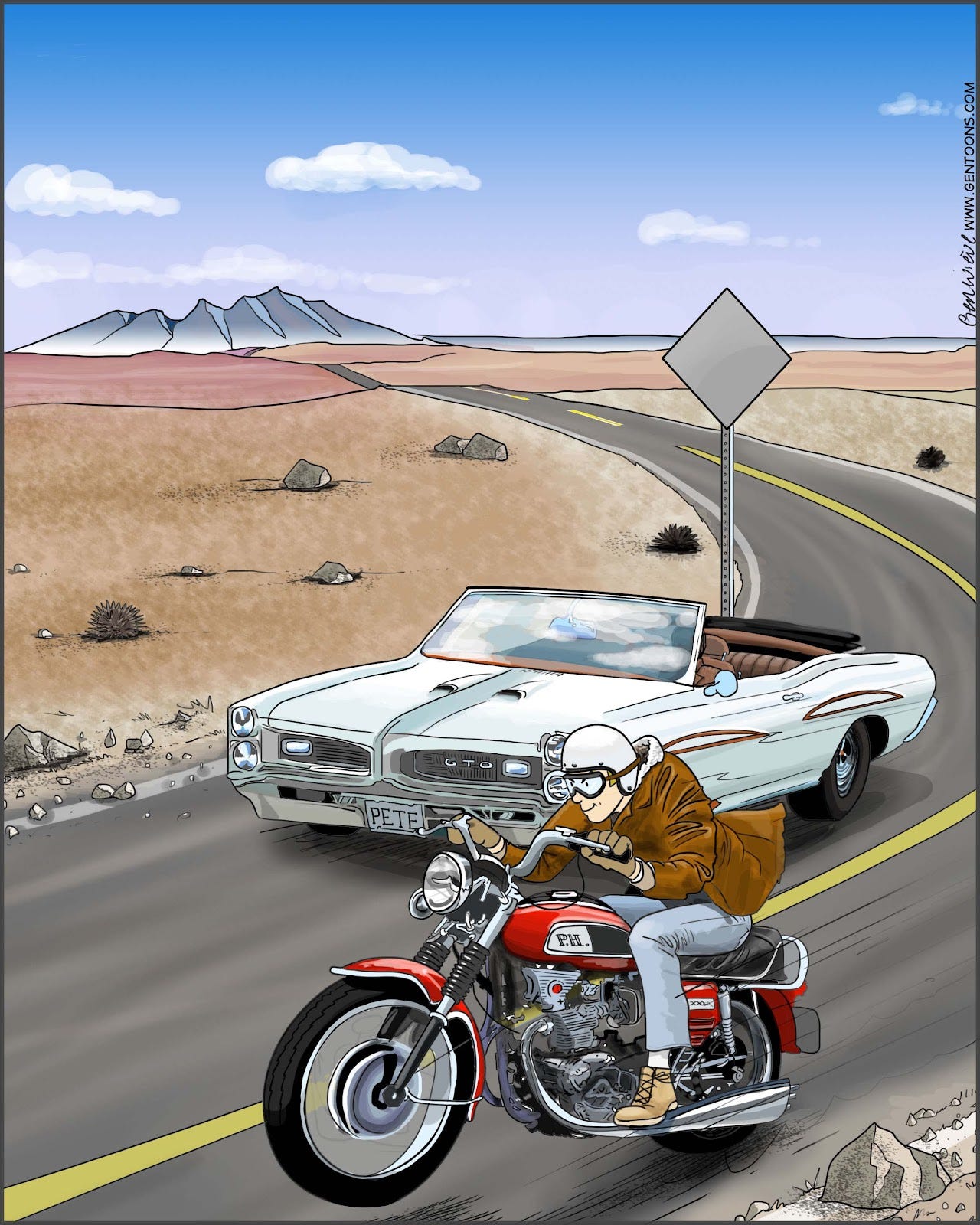

The next day I was back on the flat desert highway. It was straight and flat as far as the eye could see, free and clear to the vanishing point on the horizon. In those days, Nevada had no speed limit, so I took advantage. I was doing about 80 miles an hour in the middle of the empty desert when a brand-new convertible Pontiac GTO pulled alongside me. The driver was a well-dressed businessman who kept stepping on the gas, tempting me into a race. As he stepped on the gas again, I slowly opened the Rocket’s throttle and this time didn’t let up. Before long, the speedometer read over 120 mph and I had my chin planted hard on the tank. The speedometer kept climbing, climbing, climbing,... until its mechanism strained and broke. It simply couldn’t keep pace with the Red Rocket’s engine, which kept going strong. The Pontiac and I were running neck and neck for a while, engines at high whine, until I slowly began pulling ahead. I was pushing the Ruby Red Rocket III to her outer perimeter, which turned out to lie just beyond what the Pontiac was capable of doing. When I pulled into the next gas station ten or fifteen minutes later, I discovered I had burned through nearly all the gas I had left in the tank (I must have run the last bit on fumes) and that chunks of my rear tire were missing—a consequence of the friction and heat at high velocity.

When the dapper businessman pulled up next to me a minute or so later in his fancy car, he said, “Son, you were really rolling back there!”

When I finally crossed the Bay Bridge into San Francisco, I could smell the coffee from the Hill’s Brother Coffee factory below. I later met up with Pat, who had arrived on the bus to the city just after I did. A few days after that, we rode the Rocket III down Route 1 along the coast to Southern California, past Malibu through Santa Monica and Los Angeles to the town of Anaheim (of Disneyland fame) trying to figure out what to do next. We chose Anaheim of all places because it was in the heart of Orange County and we had heard that there were orange groves nearby. For we East Coasters accustomed to rougher climes, the idea of orange groves evoked the essence of blue-skied, perpetually sunny, statistically perfect California weather. So we made a point of riding the Rocket III along the shady trails that crisscrossed the acres and acres of orange groves just minutes from downtown Anaheim. The fragrant scent called to my mind memories of the orange groves I had visited as a kid in Rio Negro, Argentina. I understand few orange groves remain in Orange County today.

*****

Pat had a degree in Plant Science, and quickly found a job in a greenhouse. While I lost track of him soon thereafter, I later heard he met a Japanese girl at the nursery there, and they eventually got married. For my part, I had no job and still had the Bank of Boston in the back of my mind.

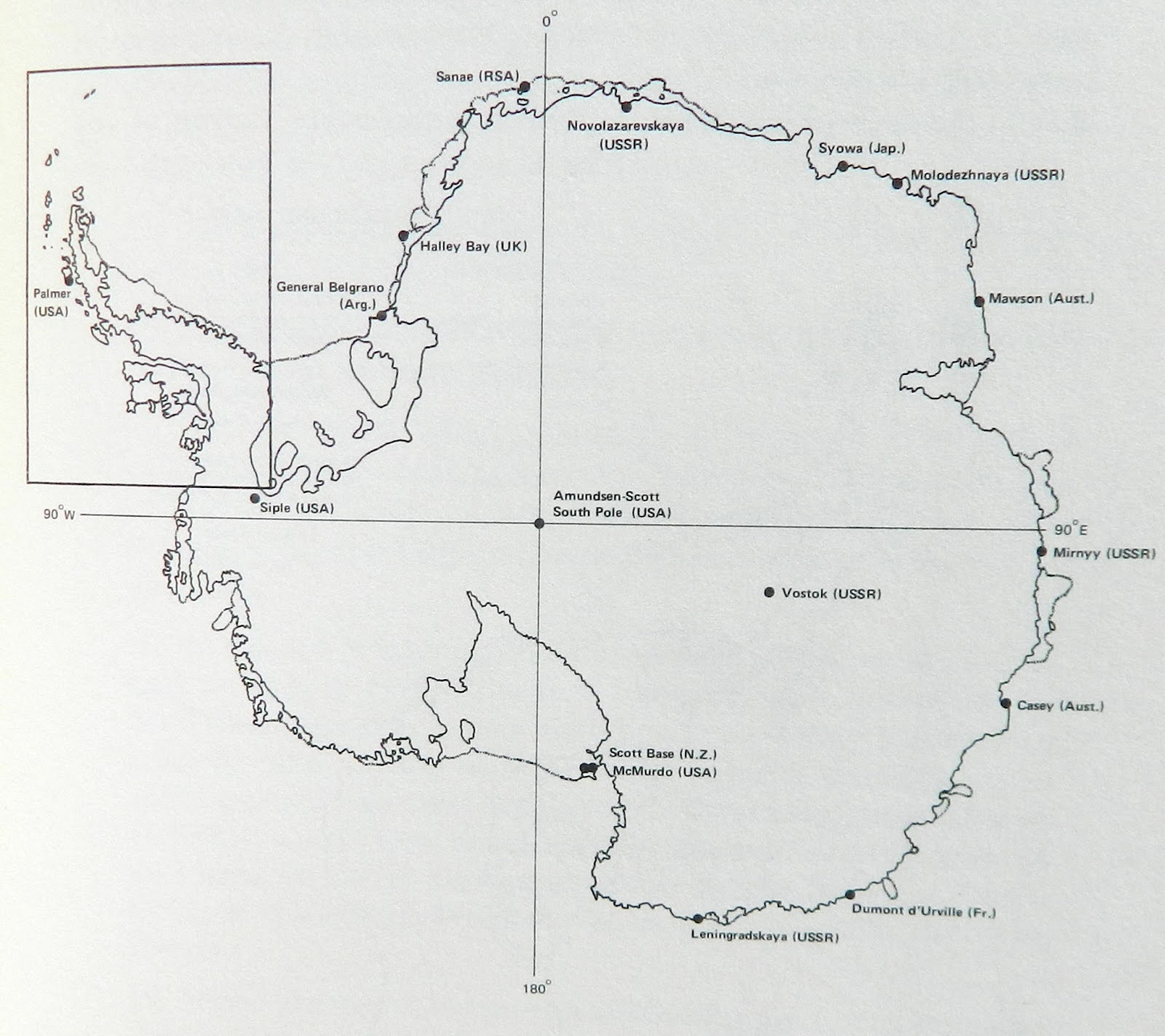

A few days later, I went to a cool cafe whose name I can’t remember in downtown Anaheim. But I recall it was the kind of place where young travelers, backpackers, hippies, and drifters like me hung out. People sat around over coffee or beer, swapping stories, telling tales about where they’d been and what they’d done. One young woman had been in Guatemala and explored the Mayan ruins of Tikal. Another had just returned from Europe, traveling by train with a Eurail pass and staying in cheap youth hostels. But the most fascinating stories by far were those of a young bearded fellow who had just returned from the U.S. Station, Amundsen-Scott, at the South Pole in Antarctica. (I later confirmed this station was named after the two famous explorers and rivals who competed to see who would be first to reach the South Pole).

We marveled. None of us knew anything about the exotic South Pole—which lay at the very bottom of the earth and was still partially cut off or even entirely missing from many world maps at the time. So when the conversations ended and people began drifting out, I took the young, bearded fellow aside and asked him how he had gotten to Antarctica.

He said, “It was easy. In fact, the office that does the hiring is right here in Anaheim, just down the street.” He wrote the address and phone number on a napkin.

*****

Interview for South Pole Duty

I shaved and cleaned myself up as best I could in the motel bathroom and made a call for a job interview the next day. That is how I came into the offices of Holmes and Narver, Inc., the contractor for the National Science Foundation’s (NSF) operations in Antarctica. Once there, I filled out the job application and was interviewed by a retired U.S. Army Colonel named Al, who had served in the same area of Vietnam that I had.

Colonel Al said, “Almost all of our jobs have been filled, and most people are looking to do a short stint during the austral summer. The only opening we have right now is for a thirteen-month winter over at the most remote and isolated station on the continent. It’s called Siple Station. It’s there to support upper-atmosphere experiments by Stanford University’s radio science lab. The position is for a Facilities Engineer and requires a four-year degree in either Civil or Mechanical Engineering. The doubles as the Station Manager. We’re in a bit of a bind at the moment because Siple Station is abandoned. Last year, there was an outbreak of hepatitis, and three of the six C-130 Hercules aircraft that service the continent of Antarctica crashed. Fortunately, no one was killed, but the problem of defective solid-fuel JATO rockets has yet to be solved. So whoever takes this position is going to be pretty much on their own. The person will have to start the facilities up cold, work hard during the few months of summer to prepare the station’s physical plant and get everything ready, and then settle in for a nine-month period of total isolation without any resupply or chance of rescue. The total population of Siple in the winter is five people. As in 5, Siple is located in Ellsworth Land, a region of Antarctica the size of Western Europe. There are no other stations in Ellsworth Land. We haven’t had anyone express interest in this difficult and dangerous assignment. Let me see your hands.”

I showed him my hands, which were dirty, cut, and deeply calloused from working as a mechanic and driving a motorcycle across the country.

Colonel Al said, “You’ll do.”

I was (provisionally) hired on the spot and began receiving a salary the following week. From that moment on, I could afford to stay in a comfortable motel in downtown Anaheim, which served as my home base for the next several months. I called my parents and asked them to tell the people at the Bank of Boston that I wouldn’t be back for another year and a half at the earliest. They didn’t sound very pleased and tried to persuade me not to do it. Going to the coldest, darkest, windiest, and most isolated continent on earth was completely nuts, they said.

My hiring was provisional because I needed to pass a battery of tests first. These tests were meant to ensure I was a suitable candidate for the stresses of prolonged isolation, among other things, and not some kind of ticking Stephen King time bomb. These psychiatric evaluations were conducted by U.S. Navy medical personnel. To do them, I was sent to three different Navy psychiatric hospitals to undergo these tests: first in Bethesda, MD; next in Newport, RI; and finally down the road in San Diego.

This last one was the most bizarre. First thing in the morning I was put in a group composed mostly of psychiatric patients who had been prisoners of war during World War II, Korea, or Vietnam. That part was pleasant enough, as I got along well with the patients, listening, bantering, even swapping war stories with them.

Later that day, the head psychiatrist, wearing a white smock and a name tag that said “Dr. Harding,” introduced himself by saying, “You and I are not related because my family is connected to President Warren G. Harding. It’s a very elite family, and I personally know all of the individual members.”

Whether he intended to intimidate, provoke, or just get on my nerves, I couldn’t tell. But his statements didn’t bother me in the least. For one, I knew Warren G. Harding to be one of the most corrupt and inept U.S. presidents in history.

If that was in fact his real name and not just part of the stress test, Dr. Harding ushered me into a tiny room with a one-way mirror and told me that everything over the next couple of days would be videotaped. The interviews alternated between a psychologist and a psychiatrist—one playing good cop, the other one bad.

My namesake psychiatrist seemed to relish his bad cop role, and began by saying, “You quit whatever job you had and told your family and friends that you were going off on this exciting adventure to Antarctica. Let me tell you what: if you don’t pass these psychological tests, you’re not going anywhere.”

I remember not being worried either way, and feeling no compulsion to respond to his taunting. They then asked me dozens of questions, sometimes replaying my answers back to me on a tape recorder to see if they could catch me in an apparent lie or contradiction.

For example, one of them said, “Look here, in this instance, it appears you favored your mother over your father, but in this other case, it seems you preferred your father over your mother. Which is it?”

My memory of the weird interrogation may be warped by a funny anecdote shared by my friend Jim Matthews just hours after his own intense session with the shrinks in the same cramped one-way-mirror room. The psychiatrist, who was puffing on a pipe during the interview, had asked Jim what he would do if a man he had just met were to make a homosexual advance. Jim replied without missing a beat, “You mean, here in this room?” This answer caused the doctor to shift uncomfortably in his chair and to cough quietly into his pipe. Both Jim and I passed the interviews. For his part, Jim later became a seasoned Antarctica veteran, eventually earning the title of “OAE, or Old Antarctica Explorer, for his long years of experience and capable contributions to life and work on the ice.

After I completed the extensive interview and testing process and got the green light to be definitively hired, the Navy medical doctors asked if I had any questions for them. I did.

“What type of person exactly are you looking for? I assume you want somebody fairly well-balanced.”

They explained they were seeking a particular personality type—one capable of putting up with some of the most extreme conditions and prolonged isolation imaginable.

“Similar kinds of testing is done for U.S. Navy ‘boomers,’ the long-distance nuclear submarines, which can be submerged for as long as six straight months and have a crew of more than a hundred. But the Antarctic winter-over program is a special case. The period of isolation is even longer, and the number of crew members much smaller. You will be going to Siple Station, a thousand miles away from the closest other U.S. base at the South Pole. You’ll live six months of the year in constant sunlight, and the other six months in constant, total darkness. Your living quarters are buried 50 feet under the ice and are quite cramped, much like a small submarine. When you come to the surface, you’ll find a featureless plain of snow-covered ice one mile thick that stretches to the horizon. Imagine being totally alone in the middle of the ocean. But to answer your question, no, we’re not looking for normal, ‘balanced’ personalities in the everyday sense. Among other things, we’re looking for people who have a high tolerance for pain, are not highly sensitive to their own feelings or suffering, but are at the same time somewhat sensitive to the feelings of others. We don’t want claustrophobic or agoraphobic people who frighten, panic, or get their feelings hurt easily. This job is not for the thin-skinned, that’s for sure.”

In preparation for our Antarctic adventure, successful candidates were sent to a succession of activities and trainings in different places throughout the United States. Beginning with a dentist, where all pending dental work, major and minor—crowns, cavities, fillings, what have you—was done at government expense. There would be no dentist in Siple Station, and no way to get to one for more than a year. I myself was also sent to a series of technical trainings. These included firefighting academies in New Jersey and California. Siple Station was loaded with all kinds of fuel and flammable materials, and, perhaps counterintuitively if you associate the presence of ice and snow with moisture or wetness, the area around it was as dry as a desert. Technical training on the Caterpillar diesel engines that powered Siple Station’s generators was also required. Keeping the generators running was a life-or-death matter in Antarctica, where temperatures could plummet to 60°F below zero. The lack of heat would quickly spell extinction for any unfortunate soul in situ. Fun antarctic survival techniques, including how to build igloos, snow caves, and latrines in the ice, were also part of the package. We would receive an expanded version of such training once we arrived in Antarctica itself.

Map courtesy of the Survival in Antarctica manual.

Our early October departure finally came. The small team of scientists and support personnel (like me) lifted off from Port Hueneme Naval Base in Oxnard, just north of Los Angeles, on a C-141 Starlifter. We flew first to Honolulu, Hawaii, and from there to Pago Pago in American Samoa, and finally to Christchurch, New Zealand. In Christchurch, the launch point for most travel to Antarctica then and now, we were issued our specialized Antarctic gear. This included parkas, anoraks (a lighter jacket), bunny boots (inflatable rubber boots), mukluks (multi-layered soft boots), special gloves and mittens, long underwear, etc. From Christchurch, we were sent down to McMurdo Station, the formal gateway to Antarctica and the largest and most populated place on the continent. McMurdo hosts the Antarctic operations of the National Science Foundation, the U.S. Navy, and various other national and international scientific and related organizations. After several final weeks of training and preparation in McMurdo, I was flown some 1,350 nautical miles to Siple Station, where I landed in mid November 1976 and remained until February 1978. I will save my Antarctica stories for another time.

*****

Bye Bye Red Rocket III

The last time I saw the Red Rocket III was when Pat Morley and I parted ways in Anaheim back in August of 1976. But I’ve thought about that beautiful bike a lot, from time to time, ever since. I’ve thought about the bike itself and about the role it played in getting me out the door and on the road, launched into the orbit of what would become the rest of my life before it fell into my memory like a booster rocket. First California; then two back-to-back winter-over tours in Antarctica; graduate school in diplomacy at the Fletcher School (I submitted my application from the South Pole); a 30-year career in the Foreign Service spent in ten countries on three continents; meeting my Burmese wife Kethi during my diplomatic posting to Africa in the Federal Islamic Republic of Comoros, where she was working as a medical doctor; our three children, now grown...

My eight-day, 2,800-mile ride across the country on Red Rocket III in the early summer of 1976 turns out to have been a critical link in the chain of seemingly happenstance circumstances, opportunities, and decisions that shaped everything that followed, separating what might have been from what turned out to be. It took me away and brought me back home full circle. Yes, I’ve thought a lot about that bike, particularly now as I ride my 1968 650cc Triumph TR6R through the bucolic back country of Western Massachusetts, the place I returned to settle down after my retirement from the Foreign Service in 2012. I sometimes find myself hoping my friend Pat never sold that bike, and kept it forever. Just in case, I have a memento of a Red Rocket III Flash Gordon muffler hanging on the wall of the workshop behind my home to remind me of that trip and everything else, too.

Pete Harding retired in the hills of Western Massachusetts. He appears above with his winter-over jacket from Siple Station and Palmer Station, motorcycle racing leathers, and his camouflage tropical uniform shirt from Vietnam.

I knew Pete from our time in the US Embassy in Peru. One of the best guys I’ve had the pleasure of meeting in my 30 years in the Army. Pete is one of those people who do what they say they are going to do-period. And so he is living in western Massachusetts—beautiful but a frozen snow globe in the winter. I just couldn’t conceive of someone retiring out there.

Indeed. Just spoke with him, and read him your note. He mentioned the time you went to the altiplano around lake Titicaca and were suddenly surrounded by alpacas like some kind of ancient ritual. Nice. Happy holidays.