“Braden or Perón”

A Past Instance of US Foreign Policy Backfiring in Spectacular Fashion: A Preview of Coming Attractions on a Massive Scale?

The march of folly in politics and foreign policy has played out in bright lights on center stage these past few weeks. The systematic assault on friendly neighbors, the targeting of the foundations of trust inside and outside our borders, the dismantling of an international system that has done more good than many Americans know, all of it feels absolutely stupid and self defeating. What might the long term consequences be? Contemplating the perversity, the senselessness, the inanity of it all, I recalled an infamous instance of US foreign policy backfiring in spectacular fashion—with lasting corrosive consequences for our diplomatic relations. But that profound policy mistake, which took place at a similar hinge moment of history, feels downright quaint by comparison. I suppose those who forget the failures of the past are condemned to repeat a far worse version. Imagine all the actions currently underway producing effects, across the board, that are decisively and diametrically opposite to the ones intended.1 It would be a start.

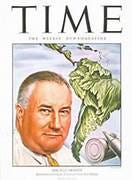

I’m thinking about the notorious tenure of Ambassador Spruille Braden in Argentina, followed by his stint as Assistant Secretary of State for American Republic Affairs in the immediate aftermath of World War II (a relative footnote in diplomatic history but revealing and representative of the wide reach of folly all the same). Braden served in Argentina for only four months (from May 21 to September 23, 1945), but he is easily the best remembered American envoy to that country of all time, if not the most beloved. Ask any Argentine to name a past American Ambassador, and they’re likely to name Ambassador Braden. Quite an accomplishment.

*****

First, a bit of background on Braden. Spruille Braden was a businessman, power broker, and Washington insider, and a repeat political appointee ambassador for Democratic presidents. Heir to a mining fortune, he had extensive private sector experience in Latin America before and after serving in his various government roles, and he spoke excellent Spanish. First appointed by FDR, he served under President Truman as US Ambassador to Cuba and Colombia, among other postings, before arriving in Buenos Aires. Braden was blunt, overly sure of himself, and confident in the rightness of the US position. He was a bully in his professional ways. (Secretary of State Dean Acheson reportedly described him as the kind of bull who brought the China shop with him). But he was also savvy and smart, and he knew the terrain.

I first learned the full Spruille Braden story while serving as political counselor in the U.S. Embassy in Buenos Aires from 2010-2013 during the testy reign of President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner (aka CFK)—a moment of resurgent strain between our two nations. In a conversation with a group of young Argentine politicians, I was asked a question for which I had no good answer at the time:

“Why is the United States so anti-Peronist?”

I honestly didn’t know how to respond to that question, only sensed that I had to tread carefully. I knew enough to know that being seen as anti-Peronist in Argentina might reverberate in unhelpful ways. For starters, CFK herself was a Peronist. I also recalled a separate meeting with retired Argentine pols of the Peronist persuasion, when a political inside-type joke had made its way into the conversation. The joke, too, turned on a question, but this one with a simple answer:

“What conditions must you meet to be a Peronist?” Pause.

“You have to be Argentine.” Full stop.

Yes, in some ways Peronist and Argentine have been political synonyms in Argentina for much of the post World War II period. And Peronism has been the dominant force in the country’s politics ever since, incorporating any and every political ideology, as well as none at all. Even Argentina’s political opposition (including current President Javier Milei) defines itself mostly in opposition to Peronism. This fact connects back to Braden, and to the question put to me by the young Argentine politicians.

After some hesitation, I decided to come clean:

“I didn’t know the U.S. was anti Peronist. I know I’m not, and I’m an American diplomat in charge of our political relations. Please explain.”

That’s when I first heard about the machinations of Ambassador Braden in Argentina. Determined to fill in the gaps of my professional knowledge, I have since read a great deal about the Braden episode and related events. Among the most of useful sources is a short book titled Braden o Perón2 (Braden or Perón) by the Argentine economist, academic and diplomat, Alieto Aldo Guadagni. His book draws extensively from declassified US diplomatic documents from that time, meaning the source material is presumably unimpeachable. 😀

After hearing the story about Braden’s plotting from my young counterparts, rather than perform an empty mea culpa, I chose to double down on my identity as an American—focused squarely on the bright possibilities of the present and future rather than looking back futilely on the dark shadows cast by the past:

“Really? Just think of where our relations with Japan and Germany would be today if the Japanese and Germans thought remotely the same way you Argentines do!”

*****

It must be said that, whatever mistakes the US (and Braden himself) may have made, Argentina didn’t—and doesn’t—always do itself any favors. To Americans (and not only Americans), Argentina has often been a bit slippery, its behavior informed by a complicated mix of wounded national pride—Argentina had long been the most important player in South America and its status was slipping—and spurned affections. The only country in the hemisphere not to declare itself on the side of the Allies during WWII, Argentina remained neutral until the bitter end. It climbed off the fence in the final weeks only reluctantly, for reasons relating to its interest in joining the United Nations. Its reputation for flightiness and unreliability surely deepened American suspicions about Argentine sympathy for the Axis powers, fascism, and the Nazi cause.

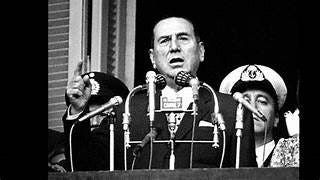

These suspicions attached with particular vigor to the figure of Juan Domingo Perón. An Argentine Army Colonel who had served for several years in Italy early in Mussolini’s rule (including a stint at an Italian military college), Perón had risen fast in Argentine politics after returning home. Critically, he participated in a 1943 coup by a group of military officers that overthrew a weak civilian government. He held a series of key positions in the de facto government thereafter. The first of these was Secretary of Labor and Social Affairs, a pivotal position which enabled him to forge close ties with the country’s powerful worker syndicates. He then became Minister of War and, soon thereafter, concurrently served as Vice President. In a failed attempt to remove him from the political scene, Argentina’s political opposition imprisoned Perón. But under the pressure of popular protests, he was freed and emerged from the episode as the country’s most powerful and promising political figure.

By the time Braden arrived in Buenos Aires as US Ambassador in May 1945, Perón was well positioned to win Argentina’s presidential elections scheduled for early the following year. As such, he represented a clear and present threat to core US foreign policy interests, the tip of the spear for the potential resurgence of fascism in South America following the defeat of the Axis Powers and the fall of Nazi Germany. The US had to pull out the stops to prevent Perón from becoming president.

Indeed, Braden arrived in Buenos Aires with clear instructions: block Perón. Braden himself, by all accounts, was a true believer, zealous in his approach to this mission, and willing to exceed his instructions, as necessary, to accomplish it. During his brief months in Buenos Aires, Braden came to be seen as the de facto leader of Argentina’s “democratic” opposition. In so doing, he became deeply and controversially enmeshed in Argentina’s domestic politics.

Braden continued his full court press against Perón after being called back to serve as Assistant Secretary of State for American Republic Affairs in Washington, with Argentina a top priority in his new and larger bureaucratic purview. In Braden’s eyes, Argentina remained the “problem child” of the Americas, requiring firm guidance and correction from the United States and its allies in the region. From this political assessment came the infamous “Blue Book” (Livro Azul3) on Argentina, formally titled “Consultation Among the American Republics with Respect to the Argentine Situation.” A Braden brainchild, this 100-plus page pamphlet of official propaganda detailed the evidence of Argentina’s connections with the Axis powers, sympathies for the Nazi cause, and likely future tilt toward fascism, should things go in the wrong direction. Protecting Argentina’s democratic prospects by preventing the election of the “fascist” Perón became the US’s paramount policy objective.

For Braden, the Livro Azul provided the “factual” justification for this policy, and was distributed to governments throughout the region just weeks before the election. The goal: tear down Perón in the eyes of the people and torpedo his presidential candidacy. Importantly, the US Embassy in Buenos Aires was not involved in preparing or publishing the document and, whatever reservations the career foreign service officer Chargé d’Affaires at the time might have felt, he lacked the political clout to push back on his bosses (including Braden) in Washington.

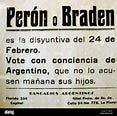

In retrospect, the result was a foregone conclusion. As Guadagni puts it in Braden o Perón, the Blue Book bomb that Braden built exploded in Braden’s own hands.

Perón, nothing if not an astute politician, took full advantage of the political opening. Pointing to the flagrant American interference in Argentina’s internal affairs and the assault on Argentina’s national sovereignty, he openly campaigned under the banner of “Braden or Perón”. It’s not hard to guess who would win that competition. Peron took a whopping 53% of the popular vote and firm control of Argentina’s government and power structure. His party won all but one Argentine state, over two-thirds of the lower house of Congress and virtually the entire Senate. Perón remained President of Argentina for the following decade, and returned to power again for a brief period in the early 70s. Meanwhile, the political movement that bears his name—Peronism—has dominated the Argentine political scene ever since.

This spectacular American own goal, a policy backfiring of epic proportions, produced precisely the opposite goal to the one intended. It is also a case study on how not to conduct diplomacy.

*****

It’s easy to perceive policy mistakes in retrospect. Did we really believe that Nazi-ism could rise Phoenix-like from the smoldering ashes of Europe, this time in South America? Apparently, yes—even if not everyone agreed or believed it with the same degree of fervency. And while it may be difficult to predict the future, in some ways (as the saying goes) nothing is so unpredictable as the past. For example, Braden was a Democrat from the left of the U.S. political spectrum, and saw the potential reemergence of fascism as the central threat in that period. He was not a Cold War Republican fretting about the spread of global communism. Such figures emerged soon thereafter. It turns out we were focused like a laser on the wrong thing. How quickly things change!

Braden himself was unfazed by the contrary evidence about Perón. Then-British Ambassador David Kelly was privately critical of Braden’s heavy-handed approach. He saw Argentina and Perón in pragmatic rather than ideological terms, through the lens of British reliance on Argentina’s beef and other agricultural exports. Braden’s successor as US Ambassador to Argentina, George Messermith, quickly came to a similar conclusion, seeing Perón primarily as an Argentine nationalist who posed no imminent danger to the United States or the region. A career foreign service officer who had served in Germany in the 1930s and been among the first to warn Washington about the rising power of the Nazi movement, Ambassador Messersmith had real credibility on this score. He began butting heads with Braden soon after arriving in Argentina.

For his part, Perón saw himself as a kind of Argentine FDR, hoping to build a modern state that supported and protected working people while energizing Argentine industry and making Argentina great again.4 After weathering Braden’s assault, Perón reaffirmed his interest in maintaining a respectful relationship with the United States. This meant that Argentina would chart its own course, cooperate with the United States (as well as the Soviet Union) when it made sense for its national interests while following the dictates of no other country. Neither fascist nor communist as it turns out, Perón was among the vanguard of the so-called non-aligned movement.

Whatever the rightness or wrongness of the US assessment about Perón at the time, one problem with Braden’s approach was its blunt, frontal, public nature. It is an axiom of diplomacy that countries pursue their own national interests, and don’t like to succumb—or be seen as succumbing—to pressures from outside in sacrificing those interests. If only for face-saving reasons, countries don’t like being made to say “uncle”. Most countries will predictably and stubbornly resist overt outside pressure for that reason. Their backs will stiffen. As we would do in similar circumstances, they will dig in and prepare to fight back if necessary. (It will be interesting to see how far Canada, Mexico, Panama, Denmark et al will go to resist overt US demands today, though it’s pure folly that we chose to test the proposition in this unnecessary way.)

*****

Having learned what might be called the Braden lesson, most American diplomats know that we are better off pursuing our interests quietly, in private, behind the scenes. And in general terms, carrots work better than sticks, producing longer lasting positive results. Particularly in sensitive environments (like Argentina) where national sovereignty concerns loom large, US public support for—or opposition to—candidate or issue X can constitute what we who worked in Latin America used to call “el beso de la muerte” (the kiss of death.) As the world’s dominant power, the US—like it or not—can become a lightning rod. As such, we had to take care not to offend, not to cause backs to stiffen, not to call down enemy fire on our position. Why? Because pursuing our own putative interests with reckless disregard for the interests of others tended not to work out so well in the end.

I thought we had learned that lesson.

I’m not quite willing to agree (yet) with Timothy Snyder, who argues in his latest Substack post that the aim is the destruction of our system. https://substack.com/home/post/p-156287745

https://www.buscalibre.us/libro-braden-o-peron/9789500729710/p/1403136?srsltid=AfmBOop1lfjziq-f3szYwYgnTKJhzkyXbUSFMSt9gmsP1RnLLChNlm0D

https://archive.org/details/blue-book-on-argentina-1946

Comparisons between current renegade Argentine president Javier Milei and Donald Trump strike me as skin deep but otherwise fanciful and misleading. If anything Trump is a kind of American Peron, having no real ideology other than unadulterated opportunism while focused exclusively on obtaining and maintaining power. Even their shared fondness for tariffs is notable. We’ll see whether their effects in weakened competitiveness, reductions in trade, and a shrinking economy also follow.