Frederick Douglass: A Singular Example of Diplomatic Mastery

And Not (Only) for His Role as Minister to Haiti

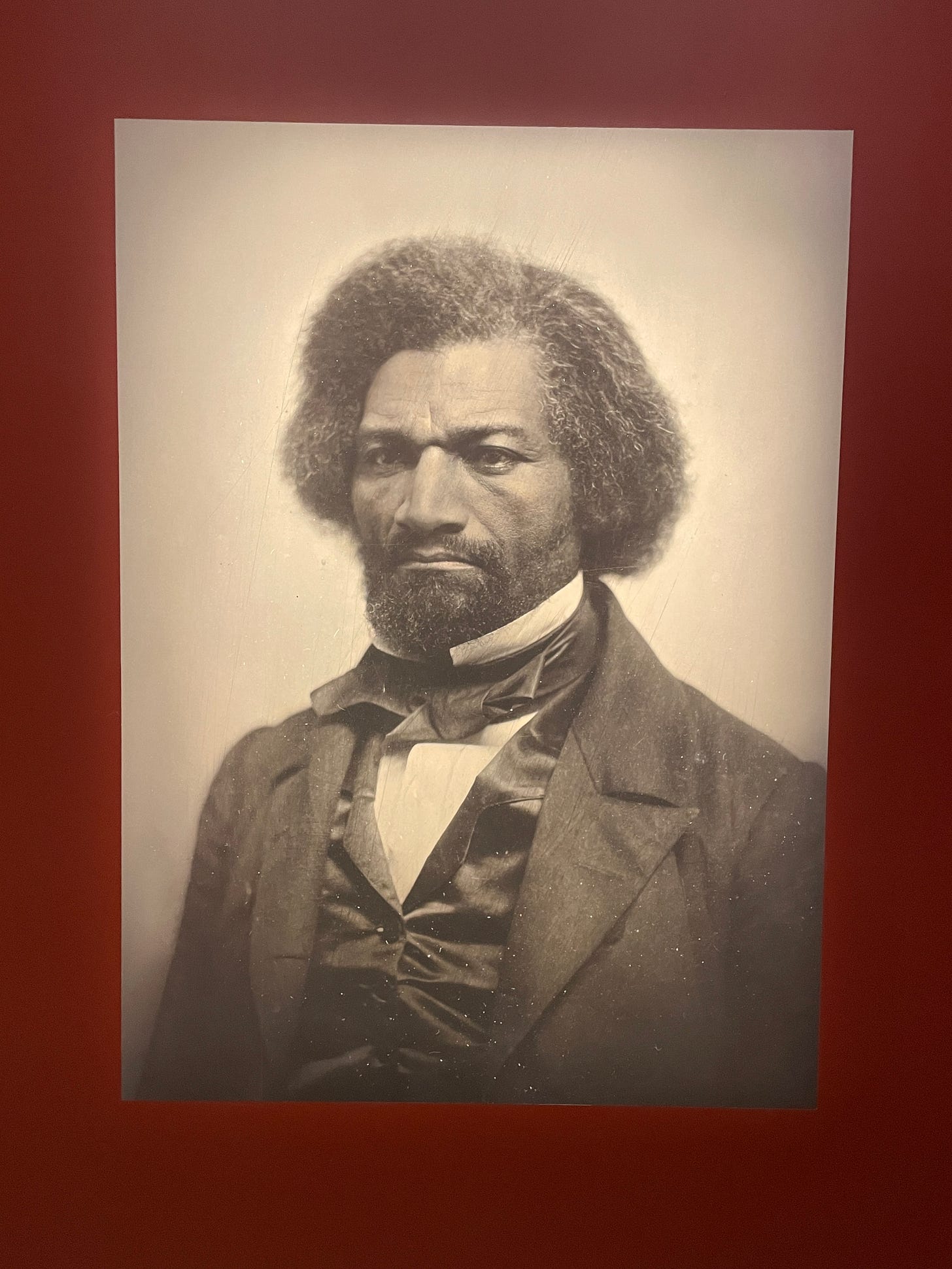

The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass is easily one of the finest works in all of American literature. If you haven’t yet read it, I urge you to do so; if you read it a while back, I’ll bet you find it worth revisiting. Douglass’s riveting personal history as an escaped slave turned renowned abolitionist, brilliant orator, and masterful writer showcases a depth of personal experience and a range of professional skills, not to mention his pivotal impact on the unfolding of US history, unrivaled in our annals.1

But when I myself read the work several years ago, one passage leapt out at me with particular force—in part because it captured the great American polymath deploying the core skills of a diplomat in as distilled and artful a fashion as I have ever found reflected in a few short pages. Why this reaction? I was serving as director for a pilot “core diplomatic skills course” at the State Department’s Foreign Service Institute (the training academy for American diplomats) and was actively searching for concrete examples of diplomatic best practices taken from the “real world”.

Before delving deeper into the passage in question, first some context. The core skills on which the course focused had emerged from a series of professional needs assessments, subject matter deep-dives, and extensive practitioner interviews—and been boiled down to three baskets:

1) Critical thinking and strategic analysis;

2) Effective communication; and

3) Adaptability to changing circumstances (particularly cultural and organizational).

If you have to condense a complex human activity down to three bullet points—and in diplomacy, you often do—these indeed are the critical skills diplomats need to master to do their job well. Outsiders might recognize them as broadly applicable to the pursuit of excellence in other, if not all professions and human endeavors. This is no surprise given that diplomacy, luckily enough for a dilettante like me, remains the last bastion of the generalist in a specialist’s world.2

*****

Now back to that passage. It was late in 1863, a critical moment for the fate of the Union and the broader cause of emancipation. Douglass had been a frequent public thorn in President Lincoln’s side, railing against his wavering on the larger questions of racial equality and the broader rights of black Americans, among other issues. But whatever his political differences with the Lincoln administration, Douglass understood the importance of a Union victory to their broadly shared strategic goals. To this end, he had been crisscrossing the country in a tireless effort to recruit black men to fight for the Union Army. By that time, questions about their courage, valor, and ability on the battlefield (and the wisdom of providing former slaves with guns and training on their use) had been resoundingly answered with the empirical evidence of repeated experience.

Pockets of opposition and resistance remained, of course, but it was a strategic no-brainer. Blacks did the military job—all aspects of it—just as well as whites did (if not better). President Lincoln himself later acknowledged that the participation of black regiments had helped turn the tide of the conflict in favor of the Union. Approximately 200,000 blacks served in the Union Army and Navy, nearly 10% of total Union forces, over the course of the war.

Predictably, however, a few problems had raised their ugly heads along the way. First, black soldiers were not receiving the equal pay they had been promised. More outrageously, black fighters captured by Confederate forces were sometimes being executed or sold into slavery—in brazen contravention to the laws of war. Third, black soldiers could not compete for commissions or promotions based on superior service in the same way white soldiers could. Douglass was beginning to feel he had been sold a bill of goods by politicians in Washington, and had unwittingly passed that same bill to the tens of thousands of black men, including his own sons, who had responded to his rousing call for service.

Uneasy in the role of faithless interlocutor whose words were not his bond, Douglass was prepared to throw in the towel on his recruiting efforts. Hearing of this, the head of black recruitment for Union forces, Major George Stearns, encouraged Douglass “to go to Washington and lay the complaints of my people before President Lincoln and the secretary of war; and to urge upon them such action as should secure to the colored troops then fighting for the country, a reasonable degree of fair play.”

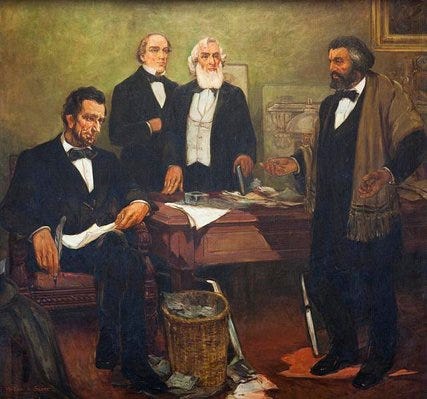

Douglass’s trip to Washington for this purpose set the stage for the storied meeting between the two men—the first time a former black slave had met in the White House with a sitting US president. I won’t dwell here on the momentous nature of the occasion or on Douglass’s private worries that he might be ignored, rebuffed, or even denied entry into White House grounds. These worries, in this case, proved unfounded. Lincoln knew Douglass by reputation (having been the object of his public excoriations on various grounds, as noted above) and understood the deeper political significance of the encounter. So the wise president was pleased to meet with the prominent black leader and eager to hear what he had to say.

For his part, Douglass was immediately put at ease by Lincoln’s kindness and open bearing. “I at once felt myself in the presence of an honest man—one whom I could love, honor, and trust without reserve or doubt.” Moreover, Lincoln conveyed a genuine interest in hearing “the particulars” of why Douglass had come. Douglass then proceeded to—in contemporary diplomatic parlance—“brief” President Lincoln on his three issues, making a special plea that “...if Jefferson Davis should shoot or hang colored soldiers in cold blood, the United States government should retaliate in kind and degree without delay upon Confederate soldiers in its hands.”

What most struck Douglass about President Lincoln was not just his willingness to listen, but his keen abilities as a listener, his manifest capacity for what might be called “deep listening” — a patient, open, purposeful kind of listening whose active aim is to discover what the other person really has to say. In view of this, Douglass felt he had the time and permission to convey his message in full. “Mr. Lincoln listened with patience and silence to all I had to say. He was serious and even troubled by what I had said... He impressed me with the solid gravity of his character, by his silent listening not less than by his earnest reply to my words.” It is no accident that Lincoln’s deep listening enabled him to absorb Douglass’s message in all its import, nuance, and detail.

Let me pause here to emphasize the point. Here was a black man, an “ex-slave, identified with a despised race” (as Douglass himself puts it) meeting with “the most exalted person in this great republic,” and being treated as an equal, being listened to with respect, being given his due as a fellow human being. “Sit down. I am glad to see you,” Lincoln had said before their conversation began. The kindness, the warm welcome, the openness, the dignified treatment, the deep listening, what Lincoln gave Douglass was worth more than gold. If one is searching for a lesson on diplomacy, one need go no further than this. Importantly, Lincoln’s respectful attitude and everything it entailed helped soften the blow contained in the mostly unwelcome substance of his response. Douglass’s summary is worth quoting in detail:

“He began by saying that the employment of colored troops at all was a great gain to the colored people; that the measure could not have been successfully adopted at the beginning of the war; that the wisdom of making colored men soldiers was still doubted; that their enlistment was a serious offense to popular prejudice; that they had larger motives for being soldiers than white men; that they ought to be willing to enter the service upon any conditions; that the fact that they were not to receive the same pay as white soldiers, seemed a necessary concession to smooth the way to their employment at all as soldiers; but that ultimately they would receive the same. On the second point, in respect to equal protection, he said the case was more difficult. Retaliation was a terrible remedy, and one which it was very difficult to apply; one which if once begun, there was no telling where it would end; that if he could get hold of the confederate soldiers who had been guilty of treating colored soldiers as felons, he could easily retaliate, but the thought of hanging men for a crime perpetrated by others, was revolting to his feelings…”

Lincoln’s deeply considered response is itself an example of deft diplomacy, not to mention political astuteness. The president was taking Douglass’s serious message with the seriousness it deserved, and answering it point by point without pulling punches. (The passage also happens to be a brilliant memorandum of conversation by Douglass, as Foreign Service officers will recognize—a clear and concise written summary of the central points in a longer verbal exchange.) Appreciating the generosity if not the content of the President’s response, Douglass goes on to write that “…while I could not agree with him, I could but respect his humane spirit.” Bingo. That’s often the heart of the matter, or at least a big part of it. If only we knew that carrying ourselves with decency, with “humane spirit”, is (with obvious exceptions) more than half the battle—in diplomacy, politics, and all other human endeavors, too, including and especially if we disagree.

But the passage does not stop there. Douglass concludes his crisp memorandum of conversation by summarizing Lincoln’s reaction to his final concern: “On the third point he appeared to have less difficulty, though he did not absolutely commit himself. He simply said that he would sign any commission to colored soldiers whom his secretary of war should commend to him. Though I was not entirely satisfied with his views, I was so well satisfied with the man and with the educating tendency of the conflict, I determined to go on with the recruiting.” For President Lincoln, this outcome was mission accomplished.

*****

But for Douglass—and for us in examining his supreme skill as a diplomat—the crux was about to come: “From the president,” he writes, “I went to see Secretary Stanton.” (Italics mine.)

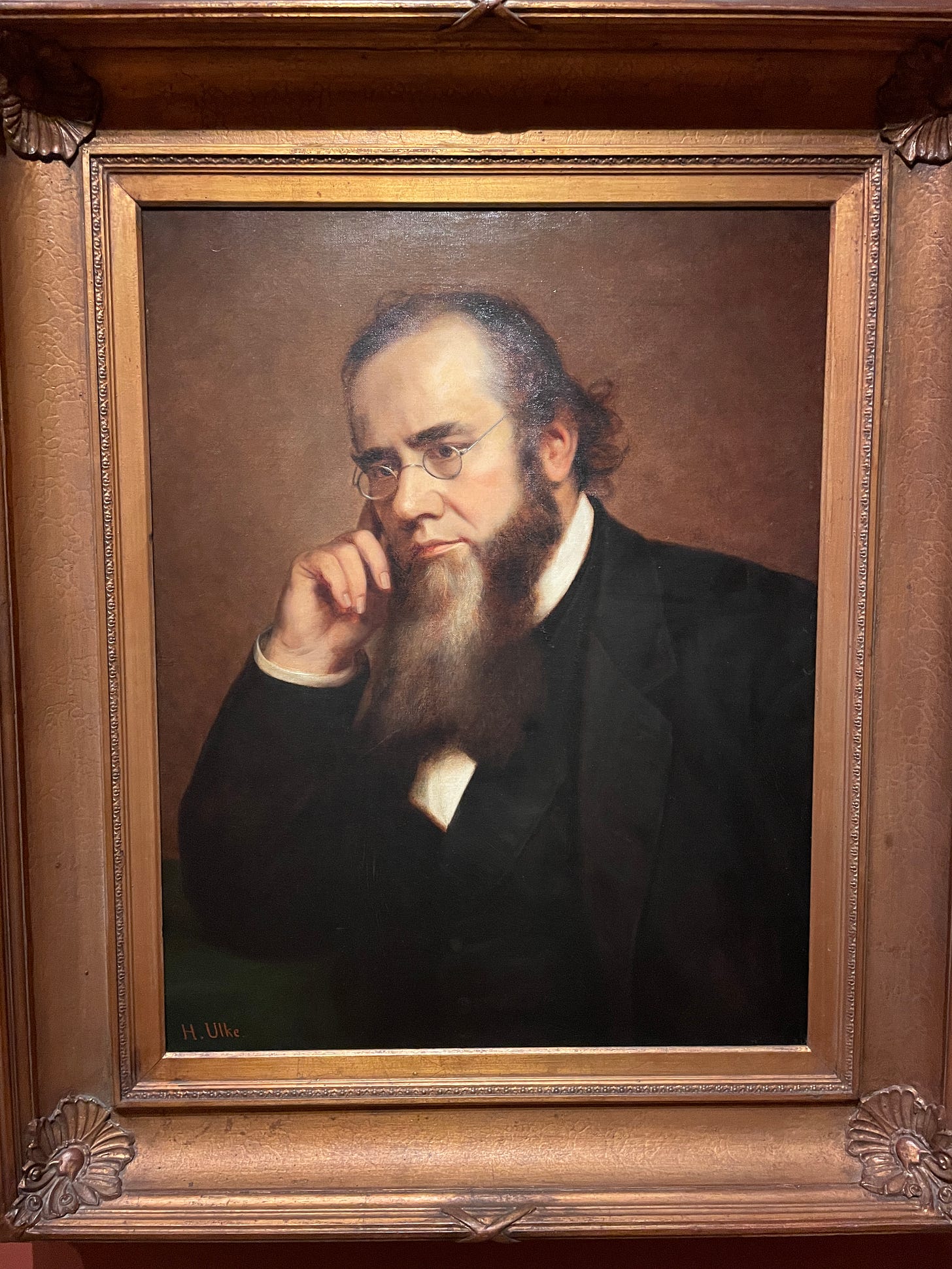

I will pause again here. For those readers familiar with the core cast of characters of our Civil War history, you already know what this name means. For others, let me fill in the blanks. In a sentence, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton was the kind of hyper-competent, hard-charging, indefatigable bureaucratic operator who got shit done without worrying about bruising the feelings of others while doing it. He was a kind of combined Richard Holbrooke/Bob Zoellick squared. (These references date me, I know, but our bureaucratic leaders today are no longer encouraged or allowed to behave in this way.) Sometimes described as Lincoln’s “irascible autocrat” among other illustrative monikers, let’s just say that—as Ron Chernow writes in his fabulous biography of Ulysses S. Grant—Stanton was the kind of boss who “enjoyed barking orders at terrified subordinates.” Now back to Douglass:

“The manner of no two men could be more widely different… Every line in Mr. Stanton’s face told me that my communications with him must be brief, clear, and to the point; that he might turn his back on me as a bore at any moment; that politeness was not one of his weaknesses. His first glance was that of a man who says, ‘Well, what do you want? I have no time to waste upon you or anybody else, and I shall waste none. Speak quick or I shall leave you.’” It is hard to imagine—and yet easy to picture—the jolt that such an encounter might produce on someone like Douglass, who (it bears repeating) had just met with Stanton’s own boss and been given all the time and space he needed to make his case.

Keeping his cool under pressure, Douglass took quick measure of the man and proceeded accordingly: “Seeing I had no time to lose, I hastily went over the ground I had gone over with President Lincoln. As I ended, I was surprised by seeing a changed man before me. Contempt and suspicion and brusqueness had all disappeared from his face and manner, and for a few minutes he made the best defense that I had then heard from anybody of the treatment of colored soldiers by the government. I was not satisfied, yet I left in the full belief that the true course to the black man’s freedom and citizenship was over the battle-field, and that my business was to get every black man I could into the Union armies.” Seeing in Stanton a strikingly different personality from Lincoln, and one who required a dramatically different tactical approach, Douglass had shifted gears, spoken “hastily”, probably in compact bullet-like points, and successfully squeezed his message through. Bullseye!

*****

I knew I wanted to use this passage for the core diplomatic skills course we were building. But how? Where should I put it? Which of the three categories of skills did it best embody? It was clearly a vivid example of critical thinking—taking the measure of a situation or person and making one’s best judgment about how to respond. (Moreover, to avoid unintended negative consequences, the judgment needs to be sound.) It was also an excellent rendering of effective communication—understanding the disposition or point of view of the other person or group and making your case in a way that will resonate, for your side and theirs.

Finally, it was the very picture of adapting quickly to changed circumstances. If President Lincoln had put Douglass at ease and given him the permission to present his case at his own pace, Stanton had decidedly not done the same thing—at least not at first. Douglass saw at a glance that “patience”—I love the searing irony of this phrase, which brilliantly conveys the character of the man in a few well-chosen words—”was not one of Stanton’s weaknesses”. So he knew he had very little time, and that a succinct, highly accelerated approach to his brief would be required for any hope of success.

How familiar that challenge seems even to those of us who have faced lower-stakes variations on the same! Seasoned diplomats know they need to be prepared to deliver the 30-second version, the 3-minute brief, or the more evenly paced 15-minute or half hour presentation, depending on the circumstances. Deploying the wrong version at the wrong time can backfire or produce nothing at all; we’ve all seen it happen. Douglass, a smart man, a perceptive observer, and a supremely capable diplomat, read the situation perfectly, quickly pivoted, and delivered the correct version of his brief at the right time, keeping the terrain open for further progress thereby. (A successful 30-second briefing can often invite follow-up questions, and the opportunity to expand on important points—just as Douglass suggests occurred with Stanton.)

Moreover, Douglass’s approach was informed by a consistent strategic calculus throughout. The problem was the plight of black soldiers which, left unaddressed, could undermine their continued recruitment—to the detriment of the Union cause they all shared. The objective was to raise the awareness of the President and his Secretary of War, with the hope that they would take concrete steps to address the problem for the benefit of that same cause. How Douglass got from defining the problem to achieving the objective depended on the circumstances or, in this case, the character of the person in front of him. He was prepared to make adjustments, and nimbly did so, as necessary, along the way. Strategic logic in a nutshell.

For my own humble purposes, after experimenting with one option and another, using this passage to kick off discussion of each core skill-set in turn, I ultimately chose to place Douglass’s example of diplomatic mastery as the course’s overarching frame. If Douglass deftly deployed each one of these core diplomatic skills in discrete ways, taken as a whole his actions also represented a superb fusion of all three wrapped into one. The passage could fit anywhere and everywhere in the course, but it fit front and center best.

*****

It is important to note that successful diplomacy does not always result in clear and measurable gains. More often than not, it can feel like a wash. Douglass himself walked away with little concrete from his Washington meetings. Even the military commission promised him by Stanton failed to come through. Did he himself meet his strategic objectives? One answer is plainly no. Another (probably) better answer is that his meetings engendered some degree of mutual understanding and an important measure of good will. Douglass also emerged from the meeting as a fervent supporter of Lincoln’s reelection, which (given the alternatives) was a decided plus for all concerned. Meantime, he was determined to redouble his efforts to recruit black soldiers—to the benefit of the Union cause and, ultimately, of emancipation for black Americans too.

*****

Looking back on that moment from the perspective of today, in the light of the (admittedly, lesser) divisions we face, we must first conclude that we are players in an infinite game. Gains are followed by losses, progress by reversals, lurches to the right by push-backs from the left, and vice versa. Nothing is permanent, least of all victory. Still, a dose of Douglass’s passion and diplomatic dexterity, coupled with a sprinkling of Lincolnesque pragmatism and (fingers crossed) humane spirit, could do us well. Who knows? It might even help us overcome our current obstacles, and get us closer to where we want and need to go.

Assessments of Frederick Douglass as a diplomat typically focus on his role as the United States’ second official envoy to Haiti following Ebenezer Basset, an episode that is covered briefly at the end of the Life and Times. I focus here on his diplomatic skills writ large.

Not everyone agrees with this description. Some critics of contemporary diplomatic practice believe we need to establish a defined professional doctrine and systematically pursue technical expertise to better achieve our professional ends, along the lines of what is done in other professions like military affairs, law, and medicine.

This is excellent.

Beautifully written and deeply insightful piece; engaging and educational as well.

Many thanks Alexis.