Executive Summary: History doesn't necessarily repeat itself and may not even rhyme, but the stunning strategic incoherence of the current US administration points in one clear direction—and it’s not across or up.

*****

Amid the frenzy of surface activity, flagrant self-dealing, and perverse unilateral dismemberment of Trump 2.0, few Americans are focused on the United States’ role in the wider world. An inward-looking people in a navel-gazing phase, most Americans don’t see the strategic “frivolity” of our current foreign policy as being among the factors most likely to inflict lasting damage on the United States and our relative position in the world, particularly in relation to the People's Republic of China (PRC).

Difficult as it is to make one’s way in a zone deliberately flooded with shit, I do. I see the current administration plunging reckless and blind down a dangerous path toward what looks to me like a wall or a cliff, which will come into view around the next bend, or the one after that… Detractors are welcome to disagree. In fact, I would look forward to hearing a cogent and compelling counterargument. Because I have yet to come across one, and I desperately want to be wrong. For the record, I found the unctuous defense of Trump’s first 100 days emanating from the ideologues at the Heritage Foundation wholly lacking in (what I used to consider characteristically American) pragmatism. It also focused narrowly on domestic score-settling and the joys of destruction, with an almost comical disregard for the bigger strategic picture and, for that matter, rebuilding.

*****

As a former American diplomat whose mother was French and whose father was German, I am struck by a striking historical parallel involving both my parents’ home countries. It’s probably more accurate to say potential parallel, given the future is no done deal—yet. For background, my father was a German academic with a keen interest in history and my mother was the daughter of a French cavalry officer. So reference to the “La Guerre Franco-Prusse” (the “Franco-Prussian War”) was heard with some frequency around our dinner table. If I didn’t fully appreciate the reference at the time, I do now. Besides, my mother was born on a French military base in the village of Sarrelouis in the Saar region, and her birth certificate noted her birth country—coincidentally—as “Germany”.

What does this have to do with anything? Let me try to explain.

France and Germany Trade Places

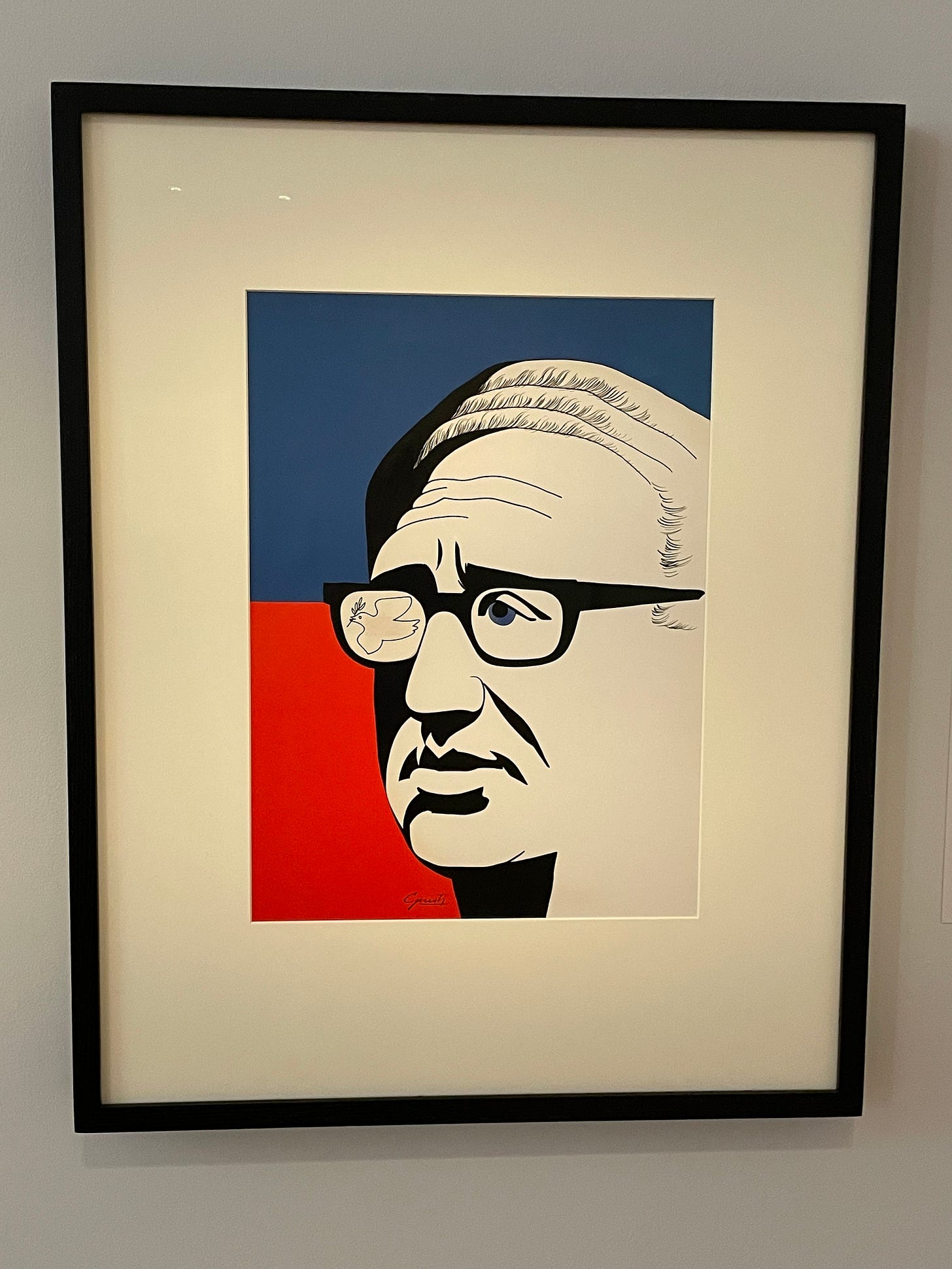

In preparing a lecture on key moments in diplomatic history for a graduate course I am scheduled to teach this summer, I happened to re-read parts of Henry Kissinger’s magisterial 1994 book Diplomacy. To briefly set the scene: From the emergence of the nation-state after the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, France became the most powerful state in Europe—a status it retained for more than two centuries. After seizing power in late 1799, Napoleon wielded France’s geopolitical dominance and the energies unleashed by the French revolution by initiating a series of wars of imperial conquest that continued for fifteen years. Following Napoleon’s massive strategic overreach born of hubris and delusion (a familiar pattern) and his definitive defeat at Waterloo in 1815, the Congress of Vienna formed the Concert of Europe. In this early modern example of a successful multilateral diplomatic arrangement, guided by the masterful Austrian diplomat Klemens Von Metternich, the war’s victors banded together to “balance” France and to prevent another Napoleon-like figure from rising to wreak havoc on the continent again.

Kissinger points out that France’s role in the 18th and 19th centuries was akin to the one Germany came to assume in the 20th—a nation to be feared for its potential lashing out with imperial ambition if its power remained unchecked.

Kissinger’s chapter titled “Two Revolutionaries: Napoleon III and Bismarck”— which focuses on the events leading to the unification of the loose Confederation of German states, the 1870-71 Franco-Prussian War, and the emergence of a newly unified Germany—is revealing in this connection. As connoisseurs know, Kissinger admired Bismarck above all other modern statesmen. Bismarck was a grandmaster of so-called realpolitick—a brilliant, cold-blooded, and ruthless, but also prudent and wise diplomatic strategist. Kissinger’s boundless admiration for Bismarck may color his analysis.

Meantime, Kissinger thinks somewhat less highly of Napoleon III. Scattered examples from relevant passages of the chapter provide the needed context and flavor. (Note: When he refers to “Napoleon” he is referring to Napoleon III, not the original).

Kissinger:

“Frivolity is a costly indulgence for a statesman, and its price must eventually be paid. Actions geared to the mood of the moment and unrelated to any overall strategy cannot be sustained indefinitely. Under Napoleon, France lost influence over the internal arrangement of Germany, which had been the mainstay of French policy since Richelieu.1 Whereas Richelieu understood that a weak Central Europe was the key to French security, Napoleon’s policy, driven by his quest for publicity, concentrated on the periphery… (and) France found itself alone.”

“France was now obliged to tend to the collapse of its historic preeminence all by itself. The more hopeless its position, the more Napoleon sought to recoup it by some brilliant move, like a gambler who doubles his bet after each loss… These prospects vanished whenever Napoleon tried to snatch them because Napoleon wanted his “compensation” handed to him and because Bismarck saw no reason to run risks when he had already harvested the fruits of Napoleon’s indecisiveness…

“Napoleon had wrought the revolution which he had sought, though its consequences were quite the opposite of what he had intended. The map of Europe had indeed been redrawn, but the new arrangement had irreparably weakened France’s influence without bringing Napoleon the renown he craved…”

“Napoleon had encouraged revolution without understanding its likely outcome. Unable to assess the relationship of forces and to enlist it in fulfilling his long-term goals, Napoleon failed this test. His foreign policy collapsed not because he lacked ideas but because he was unable to establish any order among his multitude of aspirations or any relationship between them and the reality emerging all around him. Questing for publicity, Napoleon never had a single line of policy to guide him. Instead, he was driven by a web of objectives, some of them quite contradictory… (which) canceled one another out.”

“Napoleon saw the Metternich system as humiliating to France and as a constraint to its ambitions… Overestimating France’s strength, he had encouraged every upheaval, convinced he could turn it to France’s benefit.”

By now, you get the picture.

Supplemented by biographies of Bismarck and related contextual reading, I’ve now reread the chapter from Kissinger’s book several times, to make sure I grasped its full impact. Thesis statement: Bismarck—the coldly calculating, boldly brilliant diplomatic strategist—played Napoleon III—the inveterate bluffer and blusterer who was prone to making unrealistic assumptions and frivolous gestures based on mistaken gut instincts—like a fiddle. And following the 1870-71 Franco-Prussian War, a trap Bismarck had set and Napoleon III had fallen into with blithe overconfidence before being decisively defeated, a newly unified Germany—under Bismarck’s astute leadership—emerged as Europe’s leading power while France was relegated to second-tier status. Germany also seized great swaths of French territory, including the Saar region (where my French mother was born), in the process.

The parallels seem so self-evident as to be scarcely worth pointing out.

*****

A Latter-Day Trading of Places?

Like France during the two plus centuries following the Peace of Westphalia, the United States has enjoyed almost unrivaled supremacy in the post-World War II international order. This includes the unipolar moment after the collapse of the Soviet Union and a position of virtually unchallenged global leadership ever since. Besides having by far the most hospitable and productive real estate geographically speaking in the world, America’s countless advantages have included:

an open society and a resilient if messy democracy capable of absorbing diverse cultural influences and channeling conflicting interests in a positive direction;

the world’s most dynamic economy that has not only survived but thrived through successive waves of creative destruction;

the world’s top research universities that attracted the world’s best brains and fueled cutting-edge advances across a full range of scientific, technological, and related fields;

a highly functional government and relatively sound (if imperfect) institutions;

unparalleled “soft power” in the form of our self-critical, self-correcting, always flawed but powerfully attractive example;

the most powerful military in the world even now…

The list is nearly endless.

Not least, the United States has led a sprawling system of global alliances—in Europe (NATO), East Asia (the US-Japan and US-Republic of Korea security treaties), and beyond. Most recently, we added the QUAD to the list, which brings Australia and India into a larger fold of security and related cooperation. The envy of our geographically more constrained rivals elsewhere in the world, our domestic security and prosperity have been anchored in intensive, virtually seamless relations with our two large and enormously benevolent neighbors in North America—Canada and Mexico. Speaking of Canada, I challenge any analyst or critic, foreign or domestic, to name a sovereign country with which they would prefer sharing a 5,500 mile-long land border, the longest such border in the world. Based on 30 years serving as a diplomat on three continents, plus all the related travel and study that comes with it, I can’t think of one.

*****

Not to put too fine a point on it, but I see Trump enthusiastically embracing the role of Napoleon III and the PRC’s Xi Jin Ping playing a coy version of Bismarck. (Russia’s Vladimir Putin is something else entirely, more like a supremely treacherous and dangerous Joker). For one, the PRC is explicitly identified in successive US National Security Strategies in administrations of both parties (including Trump 1.0) as our sole peer competitor and our principal geostrategic and economic rival. Of course any historical comparisons are imperfect. For one, Napoleon III was (Kissinger comments in passing) a superb manager of domestic policy, and helped build the Paris of fabulous buildings, broad boulevards, and beautiful vistas that makes it the most visited city in the world. I have trouble seeing Trump playing any equivalent role for the United States, unless using the nation’s highest public office to expand one’s global empire of private golf courses, exclusive personal properties, and (now) crypto riches can be shoehorned into that column.

For his part, President Xi is well-known for his ruthlessness, determination, and strategic patience. But it is not clear he will rise to a Bismarckian level of prudence or wisdom. This question will hinge on whether he makes his move only once the PRC has accumulated the means required to bring about his desired ends—and not before the timing is right or after it’s too late. The high-stakes game of chicken being played on the trade front right now will likely help tip the scale in one direction or the other. I (for one) won’t bet against China’s ability to endure pain longer than we can. In the short term, Xi’s ends include China taking over the “renegade province” of Taiwan, and next—depending on the nature and effectiveness of the international response—assuming leadership in its very own East Asian sphere of interest. In the longer term, his goal is to reestablish China’s historic role as the Middle Kingdom in a global order it dominates, meaning the United States would have obliged by trading places and fallen down a notch or two.

I can only imagine that our partners and allies, erstwhile and otherwise, all around the world but most acutely in Asia, are hedging their bets. If I were them, I know I would.

In following this (instructive if imperfect) historical analogy, it strikes me that the equivalent of a Franco-Prussian War might not be necessary, though a military contest over Taiwan would surely do the trick. According to most military analysts and war game scenarios, for reasons of geographic proximity, core national interests, and relevant military capability, the PRC would win such a contest handily. On the other hand, Xi would presumably prefer to preempt such a potentially messy situation, which could trigger World War III if things got out of hand (as things could). As a student of Chinese strategist Sung Tzu, Xi also knows that with careful preparation, “to subdue the enemy without fighting is the height of skill” and far preferable. In this case, Xi may simply choose to sit back and watch as his American counterpart completes the perverse and unprecedented act of America’s slow-motion (yet at the same time strangely accelerated) national suicide.

*****

In sharp contrast, driven by his quest for publicity, Trump can continue practicing the politics of pure public gesture. Before the fawning admiration of his cabinet of sycophants and the growing gallery of pro-regime influencers lobbing softball questions aimed at praising their dear leader’s unerring wisdom, he can continue playing the role of president, signing a blizzard of dizzying and disconnected executive orders for hours on end every day of the week live on national TV. He can pursue this web of contradictory objectives—imposing tariffs on friend and foe without discrimination and then removing them; destroying state institutions in the name of reforming them; gutting our constitutional protections by declaring national emergencies that don’t exist to keep us safe from dangers he has grossly exaggerated if not invented whole cloth. Overestimating his ability to influence events every step of the way, he can gain the world’s contempt instead of his desired renown while eroding our national influence irreparably. In the characteristically grand, gaudy style we have come to expect, with the camera’s clicking and the mad crowds howling with glee, he can tend to the collapse of America’s historic preeminence all by himself.

Then Mr. Xi can step quietly forward, smile a thin smile of historical recognition, to usher in the brave new world of PRC geopolitical domination. As was said once by someone important in a separate connection, it’s gonna be wild.

Cardinal Richelieu is seen by historians as the architect of the Westphalian system of nation-states.

Alexis, a fine piece of research and writing, and if I wasn't scared before (actually, I was ...) I am now. Napoleon III would be delighted with what Trump has done with the Oval Office decor!

Just two small comments for now:

Yes, the 1870/71 war is known in English as the Franco-Prussian war. (And clearly also in French as per your mother.) I think that description is not correct, the name of Franco-German war would be more appropriate. Mainly as combatants were not just from Prussia but also from other German states, including I believe the king of Wuerttemberg?

And a personal note, you've cleared up something which I had wondered about, your surname. I had wondered whether you had German roots.