The Perpetuation of Our Political Institutions

Special Guest Post by Abraham Lincoln: Address Before the Young Men's Lyceum of Springfield, Illinois, January 27, 1838

This week Unbreaking News will feature a guest post by former President Abraham Lincoln. Some readers may have heard of him.

Why this? Why now? Apart from the obvious reason, I suppose I’m trying to make the best of having been stranded in the DC area since summer 2016 (following a succession of overseas diplomatic assignments), just months before Donald J. Trump was first elected president. Riding my bike and reading U.S. pre-Civil War and other history have helped ease the wanderlust. (As David McCullough famously noted, one can be provincial-minded in both geography and time.) Whenever I bike from the outskirts of Washington where I currently live, down the beautiful Capital Crescent trail along the Potomac river past the Georgetown waterfront and the Kennedy Center to the National Mall, I tend to stop for a few minutes in front of the Lincoln Memorial.

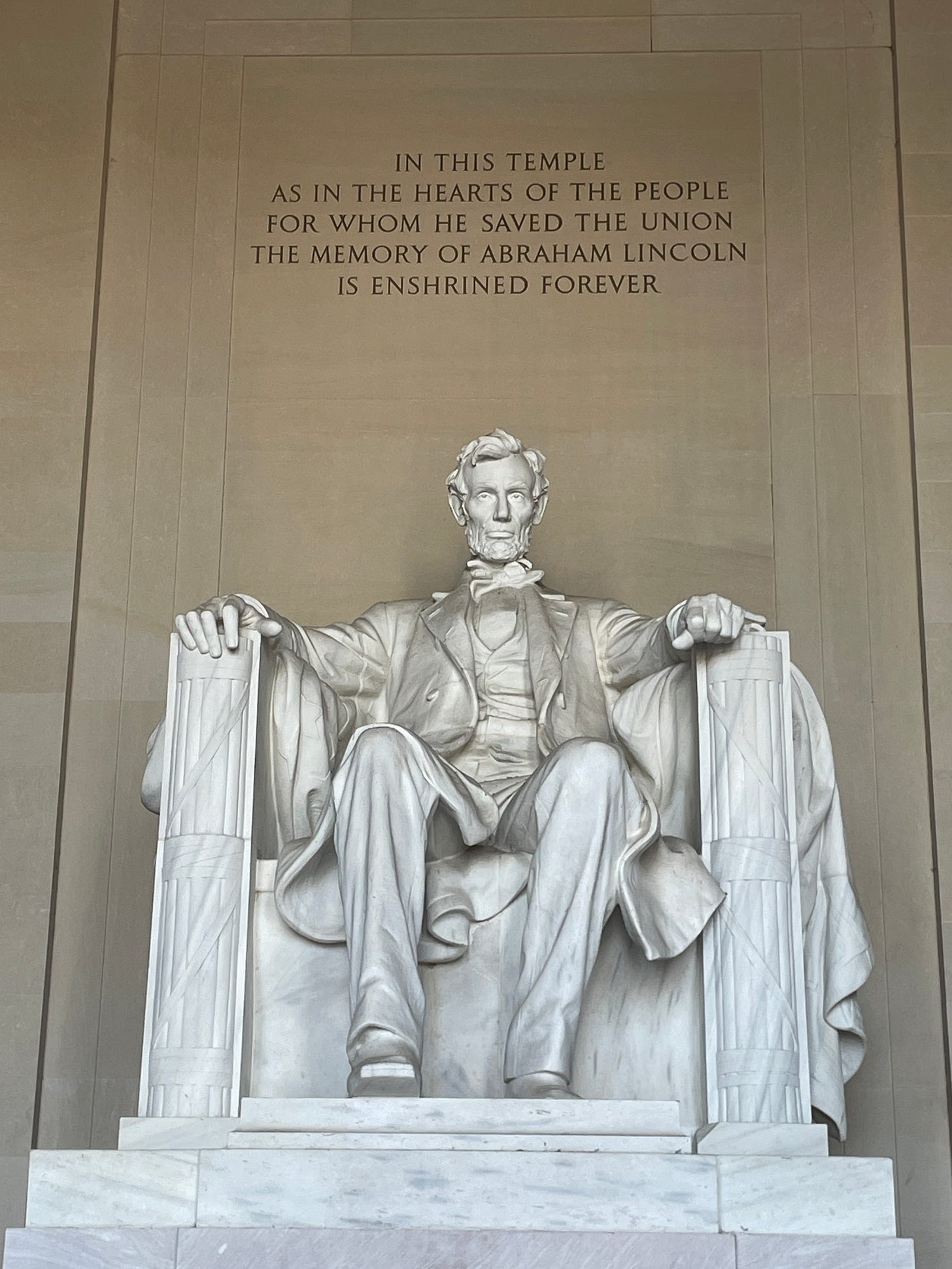

What an impressive sight! The sweeping view of the Washington monument with the Capitol dome behind it! The neoclassical temple of the memorial itself! Countless happy tourists taking pictures, selfies, group portraits on the steps and platforms above the reflecting pond. People young and old, of every color, race and creed, from all across the country and around the world, taking in the wonderful sight. I find I enjoy seeing the visitors there as much as anything else. Tourism at its best. Behold, the center of global democracy!1

These days, however, a second thought has crept into my reflections. The deified savior of the Union we behold now is nothing like the flawed, shape-shifting master politician he was in his own time. Now he sits up there lofty, expanded to heroic proportions (19 feet tall), frozen in time like a colossus, erect and unbending on his great marble seat in his great marble temple. Nonplussed by the contrast between then and now, I feel compelled to introduce him briefly here in a way that captures some of the contemporaneous criticism of him so as to better make sense of the political confusion in our own time. So here goes:

Abraham Lincoln was an uncouth and ambitious country bumpkin who lacked the credentials, if not proper preparation for high office. He was an upstart, an innocent, mostly unaware of what he was getting himself into. To think that he thought he could talk his way out of the divisions he faced—a polarization so deep, so wide and calcified that mere political bridging was no longer possible. He tried to be all things to all people a lot of the time. At heart, he was a politician—perhaps more able and honest than most, but one who wobbled and bent like the best of them, including on fundamental questions like whether all rights belonged to all people. He was hated by the uncompromising radicals on his own side almost as much as he was despised by the highly principled, self-serving racists on the other. He was mostly just trying to survive until the next round. And then what?

After emerging as the unlikeliest candidate of a newly-minted party, he took just below 40% of the popular vote in his first general election—not exactly a vote of great confidence. The second time around he was saved from near-certain electoral defeat by an 11th hour, not quite expected military victory in Georgia. (Oh, and let’s try not to gloss over the nature of General Sherman’s total war tactics just now.) Yes, Lincoln possessed the politician’s most important skill: he had the good sense to be lucky at critical times (if not always). He was never pure enough for the pure, not very godly for his time, and kept the war going for far too long. Why? Because he was a bloodthirsty tyrant pursuing a power grab, playing with the lives of millions of innocent young men to his own cynical end. Not only that, he changed his mind about the goal of the conflict halfway through—going big only after becoming aware that doing anything less would have defeated the point. You’re not allowed to do that.

Many people wanted to kill him even before he got started, and tried. In the end, he was shot dead in downtown DC by a totally delusional but absolutely convinced racial supremacist (is there any other kind?) just several paltry weeks into his second term. He hadn’t even had time to savor the tenuous military victory signed days before, much less begin the real work ahead—the still unfinished work of reconstruction. What incalculable cost has our country since paid for that colossal crime?

For good measure, he often made silly jokes at the wrong time, he was an odd-looking man with a high-pitched voice that would have rubbed focus groups the wrong way, and he wore some strange goth clothes, too. Central casting would have laughed him off the stage. The potential putdown nicknames would be legion. Just imagine. I wonder who among us today would line up on his side and who on the other. Who knows? He was pragmatic to a fault, which would seem to disqualify him in the eyes of blinkered partisans and the highly ideological on whatever side. Reading the inscription etched into the marble above his marble frame, my only question is: how long is “forever”?

Below are extended excerpts from Lincoln’s Lyceum Address. Given when he was only 28 years old, the address is said by Lincoln historians to have launched him into prominence as an orator and a thinker on the great national questions. Presaging themes reflected in his later, more famously compressed addresses given as president, he explores the role that each generation must play to preserve our democratic political institutions, to protect them from the inevitable threats that arise, and to forge them anew for the present and future. I have highlighted in bold several passages from the original that strike me as especially timely and relevant for us today. Italics are part of the original.

For those interested, the text of the full address is available here: https://www.abrahamlincolnonline.org/lincoln/speeches/lyceum.htm

The Perpetuation of Our Political Institutions:

Address Before the Young Men's Lyceum of Springfield, Illinois

January 27, 1838

In the great journal of things happening under the sun, we, the American People, find our account running…--We find ourselves in the peaceful possession, of the fairest portion of the earth, as regards extent of territory, fertility of soil, and salubrity of climate. We find ourselves under the government of a system of political institutions, conducing more essentially to the ends of civil and religious liberty, than any of which the history of former times tells us. We, when mounting the stage of existence, found ourselves the legal inheritors of these fundamental blessings. We toiled not in the acquirement or establishment of them--they are a legacy bequeathed us, by a once hardy, brave, and patriotic, but now lamented and departed race of ancestors. Theirs was the task (and nobly they performed it) to possess themselves, and through themselves, us, of this goodly land; and to uprear upon its hills and its valleys, a political edifice of liberty and equal rights; 'tis ours only, to transmit these, the former, unprofaned by the foot of an invader; the latter, undecayed by the lapse of time and untorn by usurpation, to the latest generation that fate shall permit the world to know. This task of gratitude to our fathers, justice to ourselves, duty to posterity, and love for our species in general, all imperatively require us faithfully to perform.

How then shall we perform it?--At what point shall we expect the approach of danger? By what means shall we fortify against it?-- Shall we expect some transatlantic military giant, to step the Ocean, and crush us at a blow? Never!--All the armies of Europe, Asia and Africa combined, with all the treasure of the earth (our own excepted) in their military chest; with a Buonaparte for a commander, could not by force, take a drink from the Ohio, or make a track on the Blue Ridge, in a trial of a thousand years.

At what point then is the approach of danger to be expected? I answer, if it ever reach us, it must spring up amongst us. It cannot come from abroad. If destruction be our lot, we must ourselves be its author and finisher. As a nation of freemen, we must live through all time, or die by suicide.

I hope I am over wary; but if I am not, there is, even now, something of ill-omen, amongst us. I mean the increasing disregard for law which pervades the country; the growing disposition to substitute the wild and furious passions, in lieu of the sober judgment of Courts; and the worse than savage mobs, for the executive ministers of justice. This disposition is awfully fearful in any community; and that it now exists in ours, though grating to our feelings to admit, it would be a violation of truth, and an insult to our intelligence, to deny. …

But you are, perhaps, ready to ask, "What has this to do with the perpetuation of our political institutions?" I answer, it has much to do with it. Its direct consequences are, comparatively speaking, but a small evil; and much of its danger consists, in the proneness of our minds, to regard its direct, as its only consequences….

Thus, then, by the operation of this mobocractic spirit, which all must admit, is now abroad in the land, the strongest bulwark of any Government, and particularly of those constituted like ours, may effectually be broken down and destroyed--I mean the attachment of the People. …

But, it may be asked, why suppose danger to our political institutions? Have we not preserved them for more than fifty years? And why may we not for fifty times as long?

We hope there is no sufficient reason. We hope all dangers may be overcome; but to conclude that no danger may ever arise, would itself be extremely dangerous. There are now, and will hereafter be, many causes, dangerous in their tendency, which have not existed heretofore; and which are not too insignificant to merit attention. That our government should have been maintained in its original form from its establishment until now, is not much to be wondered at. It had many props to support it through that period, which now are decayed, and crumbled away. Through that period, it was felt by all, to be an undecided experiment; now, it is understood to be a successful one.--Then, all that sought celebrity and fame, and distinction, expected to find them in the success of that experiment. Their all was staked upon it:-- their destiny was inseparably linked with it. Their ambition aspired to display before an admiring world, a practical demonstration of the truth of a proposition, which had hitherto been considered, at best no better, than problematical; namely, the capability of a people to govern themselves. If they succeeded, they were to be immortalized; their names were to be transferred to counties and cities, and rivers and mountains; and to be revered and sung, and toasted through all time. If they failed, they were to be called knaves and fools, and fanatics for a fleeting hour; then to sink and be forgotten. They succeeded. The experiment is successful; and thousands have won their deathless names in making it so. But the game is caught; and I believe it is true, that with the catching, end the pleasures of the chase. This field of glory is harvested, and the crop is already appropriated. But new reapers will arise, and they, too, will seek a field. It is to deny, what the history of the world tells us is true, to suppose that men of ambition and talents will not continue to spring up amongst us. And, when they do, they will as naturally seek the gratification of their ruling passion, as others have so done before them. The question then, is, can that gratification be found in supporting and maintaining an edifice that has been erected by others? Most certainly it cannot. Many great and good men sufficiently qualified for any task they should undertake, may ever be found, whose ambition would inspire to nothing beyond a seat in Congress, a gubernatorial or a presidential chair; but such belong not to the family of the lion, or the tribe of the eagle. What! think you these places would satisfy an Alexander, a Caesar, or a Napoleon?--Never! Towering genius distains a beaten path. It seeks regions hitherto unexplored.--It sees no distinction in adding story to story, upon the monuments of fame, erected to the memory of others. It denies that it is glory enough to serve under any chief. It scorns to tread in the footsteps of any predecessor, however illustrious. It thirsts and burns for distinction; and, if possible, it will have it, whether at the expense of emancipating slaves, or enslaving freemen. Is it unreasonable then to expect, that some man possessed of the loftiest genius, coupled with ambition sufficient to push it to its utmost stretch, will at some time, spring up among us? And when such a one does, it will require the people to be united with each other, attached to the government and laws, and generally intelligent, to successfully frustrate his designs.

Distinction will be his paramount object, and although he would as willingly, perhaps more so, acquire it by doing good as harm; yet, that opportunity being past, and nothing left to be done in the way of building up, he would set boldly to the task of pulling down.

Here, then, is a probable case, highly dangerous, and such a one as could not have well existed heretofore.

Another reason which once was; but which, to the same extent, is now no more, has done much in maintaining our institutions thus far. I mean the powerful influence which the interesting scenes of the revolution had upon the passions of the people as distinguished from their judgment. By this influence, the jealousy, envy, and avarice, incident to our nature, and so common to a state of peace, prosperity, and conscious strength, were, for the time, in a great measure smothered and rendered inactive; while the deep-rooted principles of hate, and the powerful motive of revenge, instead of being turned against each other, were directed exclusively against the British nation. And thus, from the force of circumstances, the basest principles of our nature, were either made to lie dormant, or to become the active agents in the advancement of the noblest cause--that of establishing and maintaining civil and religious liberty….

They were the pillars of the temple of liberty; and now, that they have crumbled away, that temple must fall, unless we, their descendants, supply their places with other pillars, hewn from the solid quarry of sober reason. Passion has helped us; but can do so no more. It will in future be our enemy. Reason, cold, calculating, unimpassioned reason, must furnish all the materials for our future support and defence.--Let those materials be molded into general intelligence, sound morality, and in particular, a reverence for the constitution and laws: and, that we improved to the last; that we remained free to the last; that we revered his name to the last; that, during his long sleep, we permitted no hostile foot to pass over or desecrate his resting place; shall be that which to learn the last trump shall awaken our WASHINGTON.2

Architect Henry Bacon modeled the Lincoln Memorial after the Parthenon in Athens, Greece. Bacon felt that a memorial dedicated to a man who defended democracy should echo the birthplace of democracy. (https://www.britannica.com/topic/Lincoln-Memorial-monument-Washington-DC.)

Perhaps we today might substitute the LINCOLN himself for the WASHINGTON in the original.

If you're interested, I encourage you to read more about Lincoln. Something that General Sherman said about him rings in my ears: "Of all the men I have ever met, (Lincoln) seemed to possess more of the elements of greatness, combined with goodness, than any other." Behind all the many allegations about him, and his quite able political bobbing and weaving, he was a man of great character and conviction, and I feel trite even saying it that way. I also encourage you to read the text of his Lyceum address, and take or leave my preface/introduction.

If you want to read a good example of an analysis of the current situation but one that reaches very different conclusions, I can highly recommend this one that just dropped: https://open.substack.com/pub/jameshowardkunstler/p/escape-from-psychopathocracy?utm_source=share&utm_medium=android&r=ravqy