The Three Indispensable Elements of Presidential Power

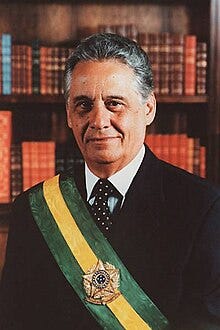

The Political Wisdom of Brazil’s (Formidable) Former President, Fernando Henrique Cardoso

One of the things I most miss about my former job as a diplomat are the conversations. You get to speak with interesting people about interesting stuff as a matter of professional course. It may be about goings-on in their country, or yours, or in the world at large. Your sparring partner may be a peer or a counterpart, and the exchange may be easy and fluid, as among friends. Or they may be an opinion leader or power broker, and your role may be to ask questions and listen.

On that note, it is not always the case that the more “important” the person, the more interesting the conversation. I’ve never been overly impressed by status in that sense, never felt the need to hang photos of the luminaries I’ve met (not that many) on my office wall. Maybe that’s because I’ve been struck as often by the banality as by the originality of so-called “important people.” I think of Joseph Epstein’s delightful essay The Bore Wars in this connection: the relationship between the social position of the person and the intrinsic interest of what they have to say can be inversely proportional. Epstein argues (and I paraphrase), that there can be nothing so boring as success, which supposedly speaks for itself. That may be part of the problem.

But there are clear exceptions to this not-quite rule. Some people rise to the top for very good reason. And it shows. One such exception, for me, was former Brazilian President Fernando Henrique Cardoso. As Embassy political counselor, I accompanied our then Ambassador and Consul General in Sao Paulo to a meeting with Cardoso—a true éminence grise and a penetrating political analyst—in early 2016. We were interested in the likely fate of then-President Dilma Rousseff back then (she was impeached and ejected from office several months later). But what I most recall now from that conversation was Cardoso’s assessment of the three key components of power that a president must possess in order to succeed—or, as the case may be, survive—in a democracy:

1) the ability to communicate directly with the people,

2) the ability to negotiate with the power structure; and

3) the ability to wield state machinery to produce results.

Cardoso’s analytical framework helped us make sense of Brazil’s then circumstances, but it also strikes me as useful for assessing political dynamics more broadly, including our own circumstances now.

FHC - Brazil’s Best President Ever

First, some context: Fernando Henrique Cardoso—or FHC as he is known in his own country—ranks as one of the most impactful political leaders in Brazil’s modern history, and among its best presidents ever. That’s my personal opinion, but I’m not alone. A renowned sociologist and scholar, he is among that rare breed of politician who successfully bridged the divide between theory and practice, moving from the distinguished halls of the academy to the highest rungs of political power. (I remember reading his foundational textbook Dependency and Development in Latin America, as an undergraduate at UC Santa Cruz.)

Following the 1992 impeachment of President Collor de Mello, FHC left his Senate seat to serve as foreign minister for the then substitute president, Itamar Franco. But it was in his next improbable role as finance minister, which (despite having no formal training in economics or finance) he was asked to assume shortly thereafter, that FHC made his first big splash at the national level. It is important to note that Brazil’s fledgling democracy remained fragile at the time, with the memory of military rule—which had ended in 1985—still fresh. Moreover, Brazil’s currency was in free-fall, inflation was soaring, and political stability was teetering in the balance again.

Cardoso’s consummate skills as a consensus builder, it turns out, mattered much more than mere technical expertise, or (in his case) the lack of it. As the saying goes in politics, FHC was “someone you could work with.” Whatever his de rigueur roots in the Latin American left, he was a pragmatist, not an ideologue. He was precisely the kind of multi-talented political figure Brazil needed to get itself out of the bind it was in at the time. In working to successfully stabilize Brazil’s currency and tame its runaway inflation, Cardoso laid down the building blocks for Brazil’s strong macro-economic foundation, subsequent trajectory of growth, and consequent political stability. Cardoso’s success in this monumental task paved the way for his election as president in 1994.

The first Brazilian president to be elected to two successive terms, FHC deepened his country’s commitment to a centrist and pragmatic policy path. He built on Brazil’s traditional status as a nonaligned power (famously a “friend to all and enemy of none”) while forging close ties with the United States. A contemporary in time and spirit to our own President Bill Clinton, with whom he enjoyed a close working relationship, FHC set Brazil on course as a rising power whose longstanding aspirations to great power status appeared, as his second term ended, to come within legitimate reach. Brazil was, after all, a continent-sized country (its land mass larger than that of the United States excluding Alaska), the fifth most populous in the world at the time (since overtaken by Pakistan and Nigeria), and a top ten global economy (depending on the year.)1

The Three Key Elements of Presidential Power

For these and other reasons, Cardoso’s assessment of the political scene carried great weight. I remember he presented the three key elements of presidential power as an interlocking package and mutually reinforcing. A minimum threshold of skill in each of these three categories was required, he said, and clear strengths in at least two. Otherwise, all bets were off. (Note: I am reconstructing this conversation from memory, and removing elements specific to Brazil for obvious reasons.)

First, presidents needed to be able to communicate their political vision clearly, in a way that resonated with something larger: the national mood, a deeper aspiration, a latent hope. This enabled them to create a direct connection with the people (“over the head of the political system”), to breathe life into their political project, and to move issues—and people—where they wanted them to go. Any president lacking this skill started with a strike against them, a steep road ahead.

At the same time, ambitious vision and high rhetoric served for little on their own. (Actors, public intellectuals, or media professionals might do this job better.) Hence, familiarity with the power structure, the so-called correlation of forces, beginning but not ending with Congress and political parties, was critical. Presidents needed not only to understand the nature of the concrete interests in play on a specific issue—the constituencies with a dog in the fight, the factions who cared for whatever reason—but to negotiate with the relevant parties and people on the basis of this understanding, preferably quietly and out of public sight. Otherwise, they might find themselves stuck in place without knowing why.

The third key component was technocratic, more mechanical than political. Presidents had to know how to wield the machinery of the state to turn ideas into actions and policies into palpable results. Many politicians foundered on these shoals. Some believed their colorful words or their artful deals would automatically translate into action or results. (They would not.) Others believed they controlled levers of power that, in fact, they did not. This was particularly notable in democracies, where a president’s actual power was diffuse and their influence often depended on indirect persuasion rather than outright command.2 Beyond that, state institutions might not be fit for purpose. So what emerged on the other side of the policy process could be vastly different and less impressive than expected.

In the end, politicians live or die by the delivery of concrete results in the form of public services and goods like security, health care, jobs, and education. Absent success in this sphere, they would not have much to show for their efforts. Broken promises or deals gone bad boded ill for their longer-term prospects.

*****

I’m hesitant to draw any broader lessons from that conversation about Brazil nearly a decade ago, though I’m tempted. We may be in the midst of a wider transformation that has upended our political order, and the tools we have at our disposal may not be the ones we need to solve the problem. But when it comes to political leadership, there is nothing new under the sun. The skills required are broad-guaged, not narrowly technical. So they transcend place, circumstance, and political moment. Among them: the ability to work with others, to communicate clearly, to listen in order to understand—including the underlying challenges and the interests in play— and, in that way, to build the necessary consensus and to deliver the needed concrete results for the people. Simple enough.

Some critics say our politics have become an exercise in nostalgia for a time that never existed. I’d prefer a less ideological, more pragmatic approach—a president who can get us out of the political bind we seem to have wrapped ourselves in and to help us take that next step.

For those interested in reading more about Cardoso, I recommend his memoir “The Accidental President of Brazil,” the English-language version of which was co-written by Brian Winter, current Editor in Chief of America’s Quarterly and among the best American analysts of Brazil.

President Harry Truman’s famous remark about the surprise awaiting General Dwight D. Eisenhower once he became president applies here: “He’ll sit here and he’ll say, ‘Do this! Do that!’ And nothing will happen. Poor Ike—it won’t be a bit like the Army.”

Excellent summary of FHC’s role and relevant contributions to our troubled country. Unfortunately, he was the last great president we have had since.

Carlos Sampaio

Yes, FHC was probably the only true statesman we ever had. His focus was on the country and its development and not on his own gains as president. Not that he didn’t have an ego - he has a huge one. So much so that he was unable to firm new leadership in his own party to carry on his legacy. Even so I still take my hat off for him for the stability he brought to an ailing and fragile democracy.