Why All These Wacky Foreign Policy Ideas?

Lack of Policy Coordination May be the Least of It -- Drawing by Genevieve Shapiro

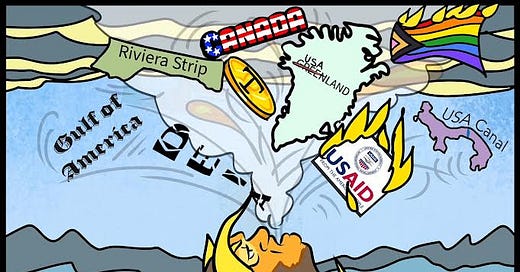

Where does one begin? Where will it end? What can possibly account for all the wild, wacky, totally unhinged foreign policy ideas that have spewed forth like an angry volcano from the start of President Trump’s second term: annexing Canada, Greenland, the Panama Canal, the Gaza strip, etc.? What the hell is next? (For the record, throwing Ukraine under the bus is a different matter, an example of unilateral dismemberment foretold. Why did it take a whole month to announce it?) One of the most obvious (if not entirely compelling) explanations is the absence of any semblance of inter-agency policy coordination or bureaucratic process.

What’s that you say? Policy coordination? Bureaucratic process? That’s boring Deep State stuff! Wasteful. Opaque. Stupid. Who needs it?

Well, we do. Because now, instead of a carefully considered menu of policy options provided by small teams of capable political appointees and seasoned career professionals representing the various federal government departments and agencies steeped in the issues in question, we now have the (apparently) off-the-cuff bright ideas of the big boss, or those of the last self-interested bazillionaire who whispered into his ear. It could be one thing on one day, and another on another, zigging and zagging with unflagging unpredictability into the nihilistically neo-imperialist, nakedly transactional future.

On one hand, “winging it” on complicated foreign policy questions yields off the wall “out of the box” thinking. It is difficult to imagine, for example, that the plan to convert the Gaza strip into a Riviera-like real estate development, led by the United States (i.e., Trump Inc.), emerged from any process, however undisciplined, of policy coordination. More like inconceivable. According to some reports, not even his closest advisors had any advance clue. But does that necessarily make the idea stupid? Well, not necessarily. Assuming a can opener, anything is possible. Since nothing else has worked, why not try something new? There may be a logic to that. Maybe.

*****

On the other hand, where to begin? One place might be “advisability”. Does the idea pass the sanity test? Does it make basic sense? Another is “feasibility.” What might the follow through—the “how” of implementation—look like? It’s one thing to announce a bright idea on TV or Truth Social. It’s another to make things happen in the real world. Do we have the ability, the will, the means? What about the costs and the risks? Are these worth taking considering the uncertain benefits? For whom?

Asking such plodding, boring, bureaucratic questions is a basic step of strategy formulation and public administration.

Trying to answer them in dispassionate fashion, particularly before announcing a plan and certainly before embarking on one, is the reason we have public institutions to begin with. I recognize the high esteem in which professional expertise is held in the current environment, but do we really want our brain surgery done by a guy who doesn’t even play a doctor on TV? (I guess I’ve just answered my own question). Let me try to make the case regardless. Involving professionals with relevant knowledge and experience from the ground floor of foreign policy formulation ensures the existence of at least some connection between ends and means, capabilities and outcomes, idea and reality. Does the Emperor have clothes? Does the thing have a prayer of coming to pass? Or does it stretch the art of the possible past the breaking point?

Critically, the people involved in generating the policy, and the departments and agencies they represent, will be the same ones called upon to carry it out. So theoretically at least, they won’t be caught by surprise when ordered to pursue a bright idea that is unachievable, ill-advised, or plain stupid. That is, if any competent professional remains to carry out anything at all after the DOGE demolition crew has come and gone.

*****

The National Security Act of 1947 was passed for good reason. When the United States emerged from the wreckage of the second World War as a great global power, the act mandated dramatic reforms to US Government organization to deal with this new reality. An ad hoc policy approach, while it may have worked to some degree for US presidents before then, was no longer seen as equal to the circumstances. Given the stakes, any kind of winging it had become too risky. The breadth and complexity of our expanded international responsibilities required a more formalized, elaborate, and disciplined decision matrix and organizational structure. Hence: “The National Security Act created many of the institutions that Presidents found useful when formulating and implementing foreign policy, including the National Security Council (NSC)”.1

Without belaboring the point, the NSC was established to coordinate what has since become known as the inter-agency policy committee process (or IPC). The idea is simple. In dealing with complex foreign policy and national security matters, we should draw from our collective knowledge and experience rather than ignore it or throw it away. No less important, we should ensure that all relevant cabinet level departments and agencies (the Department of State, the DOD, the CIA etc.) are working together rather than in isolation or at cross-purposes. Does careful coordination and smooth inter-agency cooperation guarantee success? No. But it probably increases the chances.

Take the Gaza issue again. Wouldn’t the president want to know where the bones and landmines are buried beforehand? Whether Egypt or Jordan can be counted on to comply with the sudden new demands? What we might expect from Hamas fighters as we try to clear out the 2.1 million Palestinians from the territory and implement the seaside resort plan? By the way, who is “we”? And how will the rest of the world respond—partners (should we still have them), enemies, and those in-between? Even if most Americans don’t really care, as a former diplomat I know it matters. In dealing with issues beyond our borders, it matters to a “do or die” degree. It is worth noting in this connection that IPC meetings often include representatives from relevant overseas US Missions (beamed in by video teleconference), who provide a ground truth perspective from that country or place and insight into how plan X, Y or Z might play out far away from Washington. This “outside” perspective is often seen as invaluable.

I already hear the naysayers braying in the back of my mind. “Well, if the established process worked so well, why do we still have a problem in Israel-Palestine? If so-called bureaucratic experts were such a hot thing, how did we get such spectacular bureaucratic fuck-ups as, say, the Iraq War?” Well, some problems are insoluble, with shape-shifting elements and deeply incompatible, often intractable interests in play. As such, they resist our best efforts to solve them. Israel-Palestine is one example of this kind of—in Washington parlance— “wicked problem”, where any proposed solution creates a host of fresh challenges that could as easily exacerbate as bring the original problem under control much less resolve it.

For its part, the Iraq war fiasco is better explained by the breakdown of the IPC process than by its disciplined implementation. Powerful political interests intervened to short-circuit and circumvent it. I think of the State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research warning of the grave challenges of the war’s immediate aftermath. Dismissed and ignored by the political appointee powers that be. I think of then Secretary of the Army General Eric Shinseki calling for several hundred thousand troops on the ground to ensure the victory could be sustained after the war was “won”. Dismissed and ignored by the political appointee powers that be.

Again, a smooth inter-agency process, even when managed by acknowledged experts, is no guarantee of success. Far from it. The best and the brightest acting together with discipline in a well-engineered process have brought us bad things before. (The Vietnam war morass comes to mind). But on balance, in a world lacking certainty, with success often elusive and partial at best, the systematic approach is, all told, probably a better bet. The risks of just winging it and ignoring the evidence—as evidenced in the Iraq catastrophe—may serve as a preview of more catastrophic coming attractions on a more comprehensive scale, if we’re not careful.

*****

Nobody Alone Can Fix It

Policy by fiat, by arrogance and hubris, by father knows best, by “why should I listen to all you deep state dimwits?”, is another matter entirely. Policy by hunch, by instinct or impulse, by chaos rather than control, invites all but certain disaster. Policy by “I alone can fix it” is not only stupid but self-defeating, dead on arrival, still-born. If it’s true that nothing is ever so bad that it can’t get worse, we may be about to find out how bad it can get. In Hollywood thrillers, the hero often implausibly performs, wholly on his own, multiple tasks of monumental breadth and complexity that in the real world would require a cast of hundreds if not thousands. Yet it is cliché worth repeating here that nothing—absolutely nothing—can be done alone. Raised by orders of magnitude, this fact applies to foreign policy, which is multi-tiered, complex, with many moving parts, by its very nature. As far as successful foreign policy goes, it is axiomatic—not to say a truism—that no nation can go it alone.

All told, lack of policy coordination may be the most obvious explanation for the foreign policy wackiness, but it is not necessarily the most compelling. And it feels, on reflection, rather innocent. For one, much of the madness appears pre-planned, if only to distract our attention. Moreover, judging from early polling, the president enjoys enormous popular support for the frenetic activity, which many see as progress in “fixing” the problem. For my part, I keep wondering what problem, what do we mean by “fix”, and for whom?

My early sense is, not the American people.

https://history.state.gov/milestones/1945-1952/national-security-act

This is a great explanation of why process is policy, and why process matters so much. By getting the relevant agencies around the table you can ask and answer the questions - is it possible? Is it legal? What do our allies think? Who benefits (and importantly, does the U.S. benefit)? And of course, is it good policy? In the current environment the President comes up with an idea - Gaza - and the bureaucracy scrambles to construct a policy around it, and to explain that he didn't say what he said, or didn't mean what he didn't actually say. Good process makes good policy.

Enjoyed this. Thanks.

The focus of it was on process, or lack thereof. Would love to hear your take on the substance or wackiness details of each of these wacky proposals.

I'm not an expert and, while I'm seeing a TON about the orange messenger - naturally - I'm finding very little about the message(s). I can barely keep up with the policy and initiative barrage by the admin and find myself wading through lots of responses and commentary that consist mostly of derision and vilification by "both sides", often divisive and partisan.

It's all rather frustrating! I get the "wacky" ... but why are they any more wacky than what we've seen before? And how so? I thought you got close with your discussion of the wars in Iraq, for example. At the time those wars were considered far from wacky but were positively cheer-led by most pundits and commentators, as I recall.

But in hindsight they were not only wacky but incredibly damaging -- even evil.

Which substantive features of the current crop of wacky initiatives and policies can or should we focus on in order to avoid similar levels of carnage?

Most average Americans know little about and care nothing about process points. They just want change.

Thanks again. Keep them coming.